In this one-of-a-kind, richly evocative memoir, “Everything Sad” disguises an otherworldly joy.

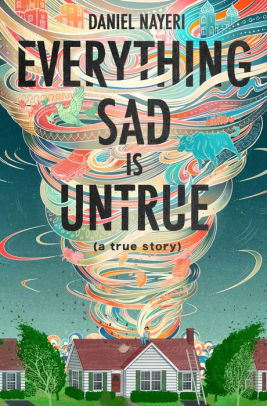

*Everything Sad Is Untrue (a true story) by Daniel Nayeri. Levine Querido, 2020, 351 pages.

Reading Level: Teen, 12-15

Recommended for: ages 13-up

All Persians are liars and lying is a sin. . . My mom says it’s true, but only because everyone has sinned and needs God to save them. My dad says it isn’t. Persians aren’t liars. They’re poets, which is worse.

As for Daniel (whose original, Persian name is Khosrou), he speaks truth through story, like Scheherazade of the 1,001 Arabian nights. She told stories to save her life, and perhaps Daniel’s motivation isn’t much different. “You’ve got my whole life in your hands”—you being us, the readers of this weird, disjointed, dreamlike, harsh, beautiful memoir. The bare facts are these: though born to a wealthy family in Iran (Mom a doctor, Dad a dentist), Daniel now lives in a crummy house in Edmond, Oklahoma, wearing thrift-shop clothes and regarded as an unappealing oddity by his 7th-grade classmates.

The reason is that when Sima, Daniel’s Mom, became a Christian, she was fatwa’d by the Islamist government and the family had to flee for their lives. Sira and her son and daughter that is; Masoud their father stayed behind. They were homeless in Abu Dhabi before going to a refugee center in Italy, where Sira relentlessly badgered the US embassy for sanctuary in the U.S. Now married to a violent abuser (also Persian, and a professing Christian), she faithfully attends church, works a minimum-wage job, and protects the children.

From the perspective of a middle-grade refugee, drawing on memory, legend, and hope, Daniel spins his story. “I am ugly and I speak funny . . . But like you I was made carefully, by a God who loved what He saw.”

Though narrated by a 12-year-old and marketed to middle-graders, Everything Sad strikes me as appealing to a more mature audience. Like Ulysses or Remembrance of Things Past (which I’ll admit never reading), it dodges among stream-of-consciousness and flashback and snapshot and myth—much the way that memory works. He doesn’t delve into sex but dwells lovingly on eating and pooping (try four pages worth). But there’s method in that, too: what better illustrates the paradox of humans, made from dust but breathed to life by God? The most moving passages relate to his mother’s conversion. When asked why she would give up a comfortable, secure life to embrace Christ, she doesn’t speak of Christianity’s therapeutic benefits, but of its truth. So—

If you believe it’s true, that there is a God and He wants you to believe in Him and sent His Son to die for you—then it has to take over your life. It has to be worth more than everything because heaven’s waiting on the other side.

That’s why everything sad is (ultimately) untrue—because there’s a bigger truth beyond it. Life here is certainly messy. We don’t understand why Sima married an abuser, and we like Daniel’s unbelieving father more than his “Christian” stepdad. But that’s life. It’s also unclear if Daniel himself is a believer, but he’s not the hero of this story. His mother is, she of the unstoppable love, “our champion, who—like Jesus—took all the damage so we wouldn’t have to.” Any reader should put this book down with the conviction that there is definitely more to living than meets the eye (or mouth, or mind, or digestive system), and it outshines any lie.

Overall Rating 5 (out of 5)

- Worldview/moral value: 5

- Artistic/literary value: 5

Consideration

- Some rough passages, such as a bloody animal slaughter at the beginning, may not be for the faint of heart.

Also at Redeemed Reader:

- Another messy but most rewarding memoir is Nikki Grimes’ Ordinary Hazards, which Betsy and I discussed here. Also see her review of Every Falling Star, an account of suffering and escaping North Korea. The semi-autobiographical novel *You Bring the Distant Near includes a similar conversion story.

- There has been no shortage of books about refugees both fictional and nonfictional. See our reviews of Refugee, Nowhere Boy, *When Stars Are Scattered, Butterfly Yellow, *Inside Out and Back Again, and Illegal.

- Another Iranian tries to acclimate to American culture in It Ain’t So Awful, Falafel.

Note: An asterisk (*) indicated a starred review.

We are participants in the Amazon LLC affiliate program; purchases you make through affiliate links like the one below may earn us a commission. Read more here.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

3 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] Daniel Nayeri’s memoir, Everything Sad Is Untrue, the author tells how his mother, a Sufi Muslim in the top ranks of Iranian society, converted to […]

I’m going to leave a comment here simply because many, like me, turn to Redeemed Reader to decide whether their reader is “ready” for a book, and while I’m so starry-eyed as to insist that _everyone must read this book_, it definitely has content that means some might not read it _yet_. I read it aloud to a 10- and 11-year-old, and I wouldn’t have have wanted to a year earlier. I’ll try to elaborate without spoiling:

– There are episodes of violence, including by children against children, many of which are more disturbing for the injustice or callousness they show than for any gore

– Domestic abuse affects more than one life; at one point depicted with some detachment but at another with galvanizing emotional impact

– An adulterous relationship outside of an arranged marriage is presented with some sympathy

– Various mythic love stories include murder, and passing mention of suicide

– Brief and passing mention is made of sex, but in a middle-school tone (“The king finds his wife in the garden copulating—that means sexing, but I use the official word because Mrs. Miller would freak out if I said ‘sex’ in class.”)

– Oh, and if you frown on any mention of poop, there might be more of it in this book than you’d like. Sometimes the “poop stories” serve as comic relief, but ultimately Nayeri admits they have a deeper purpose, that “food and poop are the truest things about you”—that which we build ourselves out of, and that which we bring forth from our hidden, inmost being.

THAT SAID… I urgently urge everyone to give this book a chance. If any of the above makes you hesitate, do yourself a favor and pre-read it yourself before giving up on it. Why is it so good? Well, as several posts on this site explicate, it’s a powerfully Christian book; it’s the parable of the Pearl of Great Price lived out. (Though it takes until the middle of the book before this theme even emerges.) But it’s also just the _best writing_ I’ve read in a long time. It’s eloquent and poetic but without for a moment becoming purple or convoluted. Individual turns of phrase are so inspired as to be pulled out and cross-stitched, while at the same time real-life anecdotes are delivered with raw candor. It makes a fabulous read-aloud, as semi-transparent layers weave and shift into and out of the narratorial voice: One moment he is a vulnerable 6th-grader delivering an oral report to the class, the next he is a slyly self-aware storyteller, weaving a Persian rug of myth and memory; the next, he disappears entirely and the recalled grandmother or mythic hero becomes the focus. The 1-star reviews on Amazon complain of the circuitous, quasi-stream-of-consciousness organization; maybe they didn’t make it this far, but toward the end Nayeri puts this charge in the mouth of his teacher and is able to defend himself: “I replied that she is beholden to a Western mode of storytelling that I do not accept and that the 1,001 Nights are basically Scheherazade stalling for time, so I don’t see the difference. She laughed when I said this. It was one of those genuine laughs you get and for a second you see the person they are when they’re not a teacher. Like the same laugh she might have at a movie or something. She said, ‘That was a wonderful use of beholden.’ And I said, ‘Thank you.'”

Thanks for this fulsome critique (and praise), Andy. We totally agree!