On Tuesday,> Janie talked about the Higgs boson, and the search for what’s under the surface in physics. Today, I’ve invited Nathan Huffstutler, a writing and literature teacher at Maranatha Baptist Bible College, to lead us on a similar search in literature. And I’m so excited to share his thoughts with you guys.

On Tuesday,> Janie talked about the Higgs boson, and the search for what’s under the surface in physics. Today, I’ve invited Nathan Huffstutler, a writing and literature teacher at Maranatha Baptist Bible College, to lead us on a similar search in literature. And I’m so excited to share his thoughts with you guys.

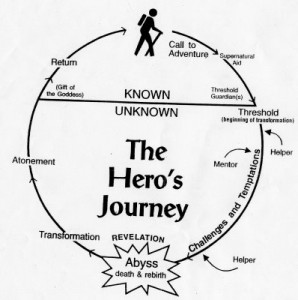

The basic idea is that many stories share the same structure, and one particular structure is The Hero’s Journey. One quick caution about the guy who developed this theory, Joseph Campbell. I am no Campbell scholar, but just reading over his book list, it seems he mixed his Christian roots with the popular liberal ideas that all religions are really the same–as if the stories of Christ making this kind of hero’s journey were no different from ones about Buddha. But of course, this doesn’t take into account that Christ was holy and could make atonement for sinners, while Budda wasn’t holy and therefore couldn’t. (It’s really a question of typology, which I’ve discussed at length in my Christ in Literature series. For a short summary, though, just remember that Created things point to God, and created heroes like Frodo Baggins aren’t just similar to Christ, but point to us to Him.)

The Hero’s Journey: A Tool to Get Developing Readers Under the Surface

As a college literature teacher, I sometimes have students in my classes who are there simply because they are getting their literature requirement “out of the way” (as they put it). But because I believe that a lifelong love of good literature is worthwhile, one of my goals is to help these students start to enjoy what they read in my classes. I want them to enjoy the practice of reading, and to be able to get under the surface of stories they encounter.

Many secondary teachers and home school parents feel the same way I do. They search for ways to get young people interested in stories and to help them see how the stories work so that they can understand the story on a deeper level—and enjoy it more.

One way that I’ve had success in getting young people more interested in the novels I teach is a story formula called the  Hero’s Journey. This formula was articulated by Joseph Campbell, an American mythologist and writer who noticed certain patterns among myths and legends throughout the world. Campbell’s book The Hero with a Thousand Faces was based on his findings. In the late 1970’s, a screenwriter named Christopher Vogler took Campbell’s formula and condensed it into a twelve-step formula that became influential among screenwriters. I use Vogler’s condensed formula in my classes. (See here for more.)

Hero’s Journey. This formula was articulated by Joseph Campbell, an American mythologist and writer who noticed certain patterns among myths and legends throughout the world. Campbell’s book The Hero with a Thousand Faces was based on his findings. In the late 1970’s, a screenwriter named Christopher Vogler took Campbell’s formula and condensed it into a twelve-step formula that became influential among screenwriters. I use Vogler’s condensed formula in my classes. (See here for more.)

When I have introduced this formula to my students, I’ve found that they connect with it immediately. Even students who previously showed little interest in literature start to open up, making connections to not just novels, but also narrative poetry (such as Beowulf), film, and even Biblical narrative.

Overview

Here’s a summary of the Hero’s Journey (in Vogler’s condensed form). I should note that you probably won’t find the steps exactly in this order in every story—but you will probably find a similar variation.

I. Separation from the Ordinary World

In the first stage of the story, the hero leaves his ordinary life in order to go on a journey or gain some sort of experience.

- Ordinary World: When the story begins, the hero is immature or inexperienced, simply going about his daily business.

- Call to Adventure: Somehow the hero receives a call to action or adventure—he is called to take up a quest or accomplish a task.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero is more interested in self-preservation, and initially refuses to go on the journey.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero receives counsel from a mentor who encourages the hero to be willing to live for a higher cause—and accept the call to action.

II. Descent into the Special World

In this stage, the hero is confronted with tests and battles that try his courage and perseverance.

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero makes the decision to attempt the journey. He is changing his values and growing in virtue.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: On the journey, the hero faces trials, and he or she meets friends and enemies.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave: The hero approaches an isolated place where danger is most intense. At this point, the hero must be willing to suffer great loss—even death—for a cause that is greater than himself.

- The Ordeal: In this dangerous place, the hero is confronted with his or her greatest fear.

- Reward: The hero survives the ordeal and gains some sort of reward. At this point, the story shows that self-sacrificing virtue will be rewarded.

III. Return to the Ordinary World

In this stage, the hero returns to a normal existence once again, having gained something positive from his experience.

- Road Back: The hero plans to complete the journey home.

- Resurrection: The hero faces a final life-and-death ordeal, and amazingly survives. This is often a miraculous escape from death. Once again, the hero demonstrates self-sacrifice for a higher cause, and is rewarded for that courage.

- Return with Elixir: Having been transformed into someone who is virtuous, courageous, and self-sacrificing, the hero returns to the ordinary world with something that brings benefit to his community. It may be an object, or it may simply be the example of his life.

The Development of the Hero Through the Journey

As I introduce this story structure, most of my students immediately make connections to books they’ve read and movies they’ve seen. But then I shift the focus from the story structure to the development of the main character. We look at how the character changes through the Hero’s Journey.

As we discuss the hero’s development, we see that the hero’s fundamental problem at the beginning of the story is his unwillingness to become committed to a cause that is bigger than himself. The hero refuses to change at first. But as he receives counsel from a mentor, and as his conscience prods him to do what is right, he starts to change his values and grow in nobility. By the end of the story, the main character has risked his life to do something good—and can truly be called a hero. He has become a different person, someone who is willing to die for something that is more important than self, and someone that the students can see, at least in some ways, as virtuous.

Hands-On Analysis

Here’s a worksheet that I’ve used to get students familiar with using the Hero’s Journey to analyze a story. In the chart I show how Bilbo (in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit) and Moses (in the Exodus story) both become less self-centered and more self-sacrificial through their journeys. As the students work through the worksheet, they can also take a favorite story of their own and see how it fits into the Hero’s Journey structure.

| The Hobbit | The Exodus | A Favorite Story of Yours | |

| SEPARATION | |||

| Ordinary World | Bilbo sits on his doorstep, calm and content (and somewhat selfish). | Moses lives in Midian with his family. | |

| Call to Adventure | Gandalf unexpectedly invites him to accompany the dwarves on their journey to the Lonely Mountain. (Bilbo is invited to change his values to help others.) | God appears to Moses at the burning bush and calls Moses to deliver Israel from the Egyptians. | |

| Refusal of the Call | Bilbo is not very interested. He goes on the journey only when Gandalf essentially makes him go. | Moses tries to persuade God that he’s not the one who should go. | |

| Meeting the Mentor | Gandalf encourages Bilbo to go. | During the story, Moses gets advice from his father-in-law Jethro, and many times he receives direction from God. | |

| DESCENT | |||

| Crossing the Threshold | Bilbo finds himself running to the Green Dragon Inn and joining the dwarves. | Moses obeys God’s call and goes to Egypt. | |

| Tests, Allies, and Enemies | Bilbo encounters trolls, goblins, elves, men, spiders, and so forth. | Moses encounters Aaron, magicians, Israelites, Pharaoh, and others. | |

| Approach the Inmost Cave | Bilbo must walk alone down the secret path to the heart of the Lonely Mountain, where the dragon Smaug lies. | As the Egyptians pursue, Moses must show great faith by leading Israel to a seemingly dead end at the Red Sea. | |

| The Ordeal | Bilbo holds a conversation with Smaug. | As Israel finishes crossing the Red Sea, the Egyptians are on their heels. | |

| Reward | Bilbo gains a goblet; more importantly, he matures in many ways as a result of his ordeals. | Because of Moses, the Israelites escape from slavery and their enemies are dead. | |

| RETURN | |||

| Road Back | Bilbo continues his quest to help the dwarves. | Moses continues leading Israel toward Canaan. | |

| Resurrection | Bilbo miraculously survives the Battle of Five Armies. | When Israel thinks Moses is dead, he emerges from Mt. Sinai. | |

| Return with Elixir | Bilbo returns to Hobbiton with self-knowledge, wisdom, and gold. | Israel’s trust (at least temporarily) in God; Moses’ knowledge of having been used of God to deliver Israel. |

So, what do you guys think? Does this seem familiar? Thanks so much to Nathan for bringing this to us!

Also, if you’d like to print this out, CLICK HERE for a downloadable copy.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

7 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I have used this material extensively with my middle school students – not just the journey archetype, but several other archetypal plot lines. They love it. It is a fabulous “organizational structure” for approaching literature. I do not consider Joseph Cambell’s work to be a Christian perspective of myth and archetype, especially since he borrowed so heavily from Jung and considers the Genesis story purely metaphorical. Leland Ryken, on the other hand, has published extensively on this subject from a deeply Christian perspective. I highly recommend his Windows to the World and Dictionary of Biblical Imagery.

Mary Kelly, Wow. Thanks for the feedback. I’m glad to hear you’ve found the information helpful. I would love to hear about the other archetypes you mention. And thanks for a little more info on Campbell, as well as pointing us to Ryken’s contribution. I will definitely check it out and put it in our eStore if it looks like something our readers need.

oh my goodness. this is a dream post! I love it so much! So much meat AND a handout? Thanks for sharing. Filing this one away for when the boys get a little older! Thanks!

So happy to hear it hits your sweet spot, Melissa. Nathan is a really fun and thoughtful reader/teacher.

Funny story: A few years ago I attended a writers’ workshop on fantasy fiction, taught by a college professor. As the professor sketched the hero’s journey (using a variation of Nathan’s 12-point outline), I watched the jaw of a fellow attendee drop lower and lower. Finally she said, “Do you realize this sounds a lot like . . . Jesus?” C. S. Lewis made the same point, in Miracles (I think that’s where I read it). In his spiritual memoir Lewis recalls an evening before his conversion, when a hard-bitten skeptic of his acquaintance remarked what a “rum thing” it was that in the gospel story, all the myths of the dying god seemed to actually come true. Campbell didn’t see the connection, but just lumped all biblical literature into the category of myth. George Lucas was strongly influenced by him, which is why the plot structure of Star Wars IV-VI follows the 12-point outline so closely.

Obviously there’s a reason why the Hero’s Journey resonates so strongly with mankind; it’s written on our hearts. Good post!

What a great story!

Great stuff! I use this with my middle school students (and up) as well. Most all of them are familiar with The Lion King so I use that to demonstrate the big concepts. Next they analyze the original Star Wars. Form and structure are beautiful aren’t they?

Blessings,

Renee