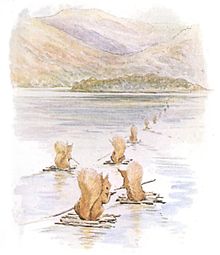

In Surprised By Joy, C. S. Lewis wrote about the flowering of his imagination at an early age–especially through books, which were piled up everywhere in his house and to which he had unlimited access over acres of free time. He read everything by E. Nesbit and Conan Doyle and Jonathan Swift, pored over Arthur Rackham illustrations and old copies of Punch magazine. But Beatrix Potter awakened him to beauty, one book in particular: “. . . I loved all the Beatrix Potter books. But the rest of them were merely entertaining; [Squirrel Nutkin] administered the shock, it was a trouble. It troubled me with what I can only describe as the Idea of Autumn. It sounds fantastic to say that one can be enamored of a season, but that is something like what happened . . . the experience was one of intense desire.” His memory jogs the illustration that always comes to my mind in relation to that story: little squirrels poling themselves on their little rafts under a dreamy autumnal sky. For Lewis, the story conjured more than it showed; something eternal, from beyond the world, planted in the hearts of men (Eccl.3:11). “It was something quite different from ordinary life and even from ordinary pleasure; something, as they would now say, ‘in another dimension.'”

In Surprised By Joy, C. S. Lewis wrote about the flowering of his imagination at an early age–especially through books, which were piled up everywhere in his house and to which he had unlimited access over acres of free time. He read everything by E. Nesbit and Conan Doyle and Jonathan Swift, pored over Arthur Rackham illustrations and old copies of Punch magazine. But Beatrix Potter awakened him to beauty, one book in particular: “. . . I loved all the Beatrix Potter books. But the rest of them were merely entertaining; [Squirrel Nutkin] administered the shock, it was a trouble. It troubled me with what I can only describe as the Idea of Autumn. It sounds fantastic to say that one can be enamored of a season, but that is something like what happened . . . the experience was one of intense desire.” His memory jogs the illustration that always comes to my mind in relation to that story: little squirrels poling themselves on their little rafts under a dreamy autumnal sky. For Lewis, the story conjured more than it showed; something eternal, from beyond the world, planted in the hearts of men (Eccl.3:11). “It was something quite different from ordinary life and even from ordinary pleasure; something, as they would now say, ‘in another dimension.'”

I was reminded of this by Emily’s post from last week on digital media. It’s a great reference post, with useful links and enlightening interview with our tech guy Michael Jones. In the spirit of exploring this new frontier, I clicked on the link for the Kirkus review of Popout Peter Rabbit and was stunned by what I saw. Children’s “book apps” have been rather academic for me; I’ve seen a few screen shots and trailers without being especially enlightened about their potential. Here’s an example of a classic story we all know, melding the original illustrations to electronic technology to create a product that’s charming, beautiful, and original.

Looking at it, I thought, That’s it. The age of literacy is over.

Right away I wonder if this is an overreaction. All technology, we’re reminded often enough, is a tradeoff. Even widespread literacy had its downside: people who could read lost some of their ability to remember. Movies, TV, computers and video games were all supposed to be the death of literacy, and all of those, especially the last two, have cut into reading time by presenting alternatives. But they don’t pretend to be reading. Even technologies that reqire some degree of literacy, like texting and social networking, don’t masquerade as literacy. But book apps present themselves as “books” and offer an “enhanced” experience of reading that may actually be something else altogether.

Picture yourself in the big overstuffed armchair with your toddler snuggled at your side, your faithful iPad in your lap. The classic Tale of Peter Rabbit shows on the screen, but what’s this? Other options to touch and open: more pictures of bunnies? Settings? Music on or off? Mommy reading or the British-accented voice on the app? Touch the cover to open the book. “Once up a time, there were four little rabbits, and their names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail . . .” Meanwhile, your toddler is touching the little falling leaves to make them pop out on the screen and drift across the text. If this is her fifth time through the Peter Rabbit app, she might get bored with leaves and ask to turn the page even before you finish reading it. On the other hand, she loves the blackberry page, because if you touch a fallen blackberry it goes splat! You may have to wait to see how big a mess she can make before turning the page. Back to the story, and naughty Peter is in Mr. McGregor’s garden–oh, what’s this? Let’s make the gooseberries roll back and forth on the bottom of the screen! What moves or pops on the next page?

It’s fun, it’s snuggly, it’s quality time, but it’s not reading. It’s a reading-themed package. The simple story doesn’t open itself to our interpretation but is interpreted for us; it comes with a Debussy sound track, British-lady voice, pop-up features and clever bells and whistles that can be poked and swiped. What gets bumped to the bottom layer of attention is the words.

There’s a difference between ebooks and book apps: the words are the last thing that matter in an app. In a book, they’re the first. A book on screen (as in the current version of the Kindle) is still a book: lines of words, an occasional static picture. An app on a phone or tablet is something else.

What three-year-old isn’t going to be so busy poking and swiping that she can give only half an ear to the words? That defeats the main purpose of a picture book, which is to supply just enough visual matter to snag their attention while they are subconsciously learning language patterns and syntax and figures of speech and the elements of storytelling. Why are children who are read to much more likely to become readers than children who aren’t? Because the necessary groundwork has already been laid. With an app, there’s so much else going on that the basic foundation of literacy may be haphazard and full of cracks.

And something else, besides verbal mastery, might get missed as well. I remember my first experience of being pierced by a book. A reader from as long as I can remember, I was always toting stacks home from the library on Saturdays and though I remember many of them fondly, none were “a trouble,” in the C. S. Lewis sense, until this one. Here’s how I ended my post about that experience: “We’re all vulnerable to something, whether music or art or dance or sailing or building or even NASCAR racing–something takes us through the surface of the day and pins us to eternity, just for a moment. Some books have done that to me, and that’s how I know I’m a reader.”

Many children–perhaps the majority–are not “readers,” in that sense. But they may never know whether they are unless they’re given ample chance to respond to words with a minimum of distraction. That’s what book apps impose upon. Let the buyer beware.

Lane Smith’s It’s a Book is a picture-book protest to digital reading, reviewed here. For further reading, browse our “Beyond Books” archive.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

5 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I agree with your overall sentiment, Janie. A sadness over the loss of a book-based culture.

I think the real issue isn’t what they are–after all, what’s wrong with a video game? But rather, what do they take the place of? When I heard about bible computer software for the first time, I reacted very negatively. I thought, now instead of reading the Bible, we’ll be walking through virtual streets of Jerusalem.

But as I reflected further, I began to ask, would Bible software take the place of reading the Bible or watching TV? In the first case it might be very harmful, but in the second, it might have some value.

When I look at book apps, I see really amazing opportunities for fun and visual experiences. And so long as it takes the place of TV or video games in the lives of kids, I’m all for them. That’s how I think Christian parents can redeem them–by not letting them replace books.

But do I think the bulk of the American public can use this self-restraint? Will most parents will continue a focus on building good readers?

The answer seems so obvious. Which is why I share your pessimism for the effect of book apps on our culture.

Yet I do believe that like video games and TV, book apps may be used harmlessly in the context of a well-balanced, Bible-based home.

That’s the rub, Emily: using new technology wisely. I don’t believe a few book apps will ruin a child for actual books–it just bugs me how they’re marketed as “reading” when, in some manifestations anyway, they really aren’t.

Excellent line. “Pinned to eternity” indeed.

Header> Popout Peter Rabbit: Chuck-E-Cheese-ifying picture books for children

Turning a child

Love your last line, George! I think it is all about the child, in the sense that we’re making him the consumer, spreading out a smorgasbord of features to choose from to customize his “experience.” I don’t have a problem with electronics once a child has learned to read–really read. But that’s not happening today.