Last August saw the 50th anniversary of The Phantom Tollbooth—has it been that long already? We’re a little late but wanted to  observe the occasion with a double review. Tollbooth is a classic of its kind: a “puzzle” story, where structure and characters contribute to the puzzle and can be used to illustrate mathematical or grammatical ideas. Since I’ve never read it (I’ll admit–it was hard for me to get into), I’m welcoming a guest poster today—who prefers to remain anonymous, but whose credibility I can vouch for. Oh–and there’s another big anniversary coming up at the end of this month. We’ll be on time for that one!

observe the occasion with a double review. Tollbooth is a classic of its kind: a “puzzle” story, where structure and characters contribute to the puzzle and can be used to illustrate mathematical or grammatical ideas. Since I’ve never read it (I’ll admit–it was hard for me to get into), I’m welcoming a guest poster today—who prefers to remain anonymous, but whose credibility I can vouch for. Oh–and there’s another big anniversary coming up at the end of this month. We’ll be on time for that one!

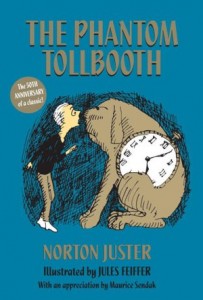

The Phantom Tollbooth, by Norton Juster. Random House, 1961, 256 pages. Age/interest level: 8-up.

Lost in Lexicon, by Pendred Noyce. Tumbledown Press, 2010, 289 pages. Age/interest level: 9-12.

Tollbooth is about a boy named Milo who is chronically bored and discontented with his life and unwilling to put forth any effort of his own to find anything interesting. A large package is delivered to his room one day which contains a mysterious tollbooth. Once Milo takes his little electric car through the tollbooth he finds himself in a another world, one of clever puns, unexpected characters and very real dangers—such as the Doldrums, the Island of Conclusions (you get there by jumping), and the Mountains of Ignorance, filled with all manner of demons. This world is separated into the Land of Letters and the Land of Numbers (led by King Azaz the Unabridged and the Mathemagician, respectively), brothers who are constantly bickering about the superiority of their own domain. Their antagonism is one of this world’s many problems, which stem from the banishment of the two princesses, Rhyme and Reason. Imprisoned in the Castle In The Air, the only way to get to them is through the Mountains of Ignorance and up the Glass Stairway. Of course, Milo takes on this quest, with the help of his new friends: Tock the Watchdog (a large dog with the body of a clock who guards against wasting time) and the Humbug (a well-dressed insect who is always trying to make himself look more important than he is). They encounter a multitude of language and mathematical concepts personified in various forms.

If this is all sounding a bit childish and simplistic, it’s because simply describing the plot doesn’t do justice to Juster’s incredible writing—it’s like trying to describe Shakespeare by some of his farfetched plots. While the characters don’t have much depth of development (OK, most don’t have any at all), they are still drawn compellingly and emotionally, with charm and extraordinary cleverness. For instance, when Milo reaches the City of Dictionopolis and is welcomed by the vociferous Ministers, they give him a ride in a wagon which has no visible means of movement, but requires its riders to be silent. Because, of course, “It goes without saying.” The reader meets the sources of color (an orchestra), sounds (the Soundkeeper, who stores all sounds in her vaults), and boredom (the Doldrums), as well as the demons of Terrible Trivium, the Senses Taker, the Horrible Hopping Hindsight, the Gorgons of Hate and Malice, and more!—not to mention words (grown on trees) and numbers (mined out of the ground). By the time Milo gets back to his own world, he is a changed boy and sees a world ready to be discovered and explored, rather than the same old boring stuff he used to see.

Since Lost in Lexicon features a world based on aspects of the written word and the manipulation of numbers, comparisons with The Phantom Tollbooth are inevitable. Ms. Noyce seems to be cognizant of this; she gives a nod to Tollbooth in the second chapter, as it is among a pile of books the children find in the barn. However, it’s not surprising that Lexicon falls short.

![]() Cousins Ivan and Daphne are spending an idyllic, if sometimes boring, summer with their eccentric but lovable great-aunt Adelaide when they are unwittingly sent to another world. There they embark on a quest which will teach them much about words, numbers, and themselves. In the land of Lexicon, regions are laid out as quadrants on a Cartesian plane, and a compass always points to the Origin: the center of the land, where the vertical and horizontal axes cross. The cousins quickly discover that the children of this land have been mysteriously disappearing. Children are sent to school at the Origin capital when they reach seven years old, but then they are never seen again. Ivan and Daphne set out to find out what’s happening to these children, and along their journey they help stop a plague of punctuation, fix a machine that works by multiplication, befriend a llama-like thesaurus, and discover the secret inside the Origin mountain.

Cousins Ivan and Daphne are spending an idyllic, if sometimes boring, summer with their eccentric but lovable great-aunt Adelaide when they are unwittingly sent to another world. There they embark on a quest which will teach them much about words, numbers, and themselves. In the land of Lexicon, regions are laid out as quadrants on a Cartesian plane, and a compass always points to the Origin: the center of the land, where the vertical and horizontal axes cross. The cousins quickly discover that the children of this land have been mysteriously disappearing. Children are sent to school at the Origin capital when they reach seven years old, but then they are never seen again. Ivan and Daphne set out to find out what’s happening to these children, and along their journey they help stop a plague of punctuation, fix a machine that works by multiplication, befriend a llama-like thesaurus, and discover the secret inside the Origin mountain.

One of the biggest differences between these two books is that Tollbooth is about the joy and fascination of learning without trying to teach anything academic (words grow on trees? Really?), while Lexicon actually explains real concepts of English structure and mathematical manipulation. To its credit, some of these could be helpful or instructive to readers who either don’t understand the concept or have never been exposed to it. In fact, the first thing that Ivan and Daphne learn is a word which may not be familiar to most readers: copula. (A copula is a small linking verb like “to seem”, or “to be,” not to be confused with “cupola”, a light domelike structure on a roof, serving to admit light or air.) Since the book is a story first, the author can’t get into any concept in significant detail, but that doesn’t stand in the way of the plot. It’s not necessary to understand any of the puzzles or challenges the protagonists encounter in order to follow what’s going on, so younger readers can enjoy it on a certain level.

While we don’t expect much depth of character in stories of this kind, the lack of character is often balanced by excellent writing and clever concepts, as in Tollbooth. Lexicon does not excel in any of these areas, which forces the shallowness of Ivan and Daphne into the limelight. Children who are a little too nice and a little too smart all the time, able to solve every challenge thrown their way while speaking in stilted dialogue, are not terribly interesting.

The bigger issue here is no recognition of a higher power in the book, or any implication that people are incapable of living truly caring, responsible lives without supernatural help. One interesting exchange between the children touches on the subject, but is not resolved: when Ivan and Daphne are inside Origin, the leaders offer them “entertainment” in order to distract them from asking inconvenient questions. For Ivan, a violent video game is supplied, and for Daphne, her favorite teen drama. However, this “entertainment” actually projects them into their fantasies. By the time Ivan crashes into Daphne’s room while pushing through an imaginary volcano they are completely disoriented and days have passed. They recognize the emptiness of their fake worlds, and Daphne asks, “‘It was entertainment custom-made for us. Doesn’t that mean that’s what we’re really like inside?’ [Ivan] said slowly, ‘I don’t know. An exaggeration, maybe. An exaggeration of one part of us.’ They tried to think, but they were too tired.” Ivan’s suggestion is the one we’re left with: we’re not all bad, but will give in to that side, given the opportunity. It’s probably the most common conclusion, but certainly not a biblical one.

A classic puzzler even older than Tollbooth is Flatland: a Romance of Many Dimensions (1884), where the characters are all geometric shapes. More an imagined history than a novel, it might amuse the mathematically inclined. Puzzlers for the picture-book set are reviewed here and here. Other quest fantasies middle readers might like are The Emerald Atlas and The Dragon’s Tooth.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

1 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thanks! I had never heard of this book. Since I usually enjoy allegories, I’m especially glad to know about it.