We live in the Age of Narrative. And increasingly, novels stop telling stories and become about story, gazing at themselves with calm adoration. This is nowhere more true than in the celebrated children’s novels of Brian Selznek.

Selnek began as an illustrator who, over time, developed a distinctive, detailed, textured style built on shades of gray. He works with shape rather than line; his pictures seem almost molded rather than drawn. The Invention of Hugo Cabret was a gamble: a novel that used pictures alternating with text, not just to illustrate his story, but to tell it. Pages and pages of drawings used perspective, tracking, and closeup much as a camera does, to visually convey action and reaction.

The effect stunned reviewers and librarians, propelling Hugo Cabret to bestseller lists, where it stayed for months. The book also seized a finalist position for the National Book Award and won a Caldecott Medal. The movie version, Hugo, premiered on Thanksgiving Day, 2011. Selznek’s next word-and-picture novel, Wonderstruck, ran to an even longer page length and appeared on dozens of “best of”/bestseller lists.

For both these books, the medium overwhelmed the message—that is, the story itself seemed less compelling than the way it was told. Maybe it’s just me, but Hugo (both the book and the movie) delivered less emotional impact than it promised. Wonderstruck, for all the built-in pathos surrounding two central characters who are deaf, seemed less a coherent narrative than a grab bag of the author’s latest interests and enthusiasms, connected in a way that’s supposed to create “wonder” but mostly creates confusion.

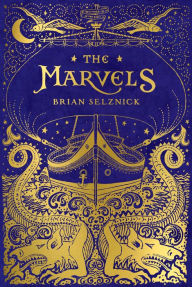

The Marvels, weighing in at 665 pages (almost 3 lb.) is his most ambitious project yet. Rather than  interspersing the visual sections, the book is all pictures for the first 400+ pages, then all text for the next 211, concluding with another, much shorter, series of illustrations. The story is less rambling than Wonderstruck and more compelling than Hugo Cabret, but toward the end it reveals itself as subversive.

interspersing the visual sections, the book is all pictures for the first 400+ pages, then all text for the next 211, concluding with another, much shorter, series of illustrations. The story is less rambling than Wonderstruck and more compelling than Hugo Cabret, but toward the end it reveals itself as subversive.

That sounds harsh, but let me refer to another novel to illustrate. Atonement, by Ian McEwan, sets up a tense, dramatic premise that resolves over the next few hundred pages. Only in the final chapter do we learn that the resolution did not happen. It was the invention of the central character, an 11-year-old girl when the story begins who eventually became an acclaimed novelist. We’ve been tricked, but the trick is the author’s way of showing how we invent stories for our own purposes: to calm a raging conscience or smooth out rumpled motives.

The Marvels does something similar, but the purpose is less clear. For the first 400 pages we are immersed in a historical narrative beginning with a storm at sea in 1766. After an intense focus on the shipwreck and rescue of young Billy Marvel, a stowaway, the story skims over time to unfold several generations of Marvels, a celebrated London theater family. An experienced Selznek reader will turn these pages slowly, noting details that will almost certainly turn up later, such as a medallion with a seagull on it. Or notice echoes in detail, as when a theater backstage in some ways resembles a ship’s lower deck. The visual section ends abruptly, after a character dashes into a fire to rescue his grandfather—

And then we’re in the black & white, text-y world of 1990. The date and the milieu will become clear later. Joseph Jensen, an English boarding-school boy, has run away from school to find his best mate and also, hopefully, to move in with his Uncle Albert in London, whom he barely knows. We see Joseph discovering things in the house that featured in the story we already know through pictures. Eventually he discovers the story itself. But there are discrepancies and disturbing elements in the tales, and finally Uncle Albert is forced to admit: “I made them up.” The pictures were drawn by someone else, to illustrate the fictional Marvels.

Joseph feels cheated—as should any reader who carefully paced through those 400 pages in order to understand what the author was trying to convey. “Stories aren’t the same as facts,” Joseph protests. “No,” replies his uncle, “but they can both be true.”

If you’ve seen Return of the Jedi, you may recall Luke’s anger at his mentor Obi-Wan for not telling him (Luke) who his father was. The ghostly Obi-Wan reassures him that the explanation he originally gave about Vader was true, “from a certain point of view.” Luke is skeptical, just as Joseph is skeptical about fact and fiction being equally true.

Obi-Wan didn’t exactly lie to Luke—he just didn’t give him all the facts.

Uncle Albert claims he didn’t lie either—he just made up the truth. Which is worse?

And which comes first: the story or the fact?

Fiction used to be regarded with suspicion by educated, rational beings. The ancients found some use for it; see Aristotle’s Poetics for his thoughts on the emotional value of tragedy and comedy. Plato used the occasional extended metaphor, and Augustine mined his own experience for illustration. But these thinkers and philosophers, if they used fiction at all, put it in service of their main business, which was the discovery of truth. Philosophical inquiry was supposed to lead to propositional statements. Truth was something you could affirm in words and discuss with further propositions. That strong preference for propositional truth probably reached its height during the Protestant reformation, with some of the most comprehensive theological dissertations ever known (not to slight Augustine, Aquinas, and the Scholastics, who were no slouches either). This was also when the discounting of fiction reached its height—a downside to the Reformation, personified by the grim-faced Puritan nailing shut the theater doors. Something of a puritanical pall hung over fiction until recently; novels were considered either a waste of time or an occasional escape from heavier thinking. The kind of truth fiction communicates wasn’t often appreciated by the scholars and philosophers among us.

I’m not sure why this changed, but I could guess it’s due more than anything to mass media. Stories surround us and consume us; the latest episode of The Walking Dead is certain to be a more relevant topic in the break room than a presidential candidate’s healthcare plan, even though the latter has more potential to actually affect our lives.

Hasn’t it always been that way? No; stories have always commanded attention and affection, but we’ve moved into an age where story shapes truth, and not the other way around. A politician’s story rings louder than his principles (see Obama, Barak, and Donald, The). One man’s narrative about events, such as the president’s interpretation of conflicts in the Middle East, carries the day even though it directly contradicts clear statements and recent history to the contrary. In the case of transgenderism, we’ve seen that even hard science can’t stand, if an individual’s neural passageways (perception) contradict his DNA (fact).

Back to The Marvels: Joseph is furious when he discovers that none of that renowned theater family, dating all the way back to the stowaway Billy Marvel, ever really existed.

“But you’re saying there was no Leontes Marvel!”

“There is. In the story.”

“But the story isn’t true! None of it matters!” Joseph’s hand gripped the edges of the case. He couldn’t bring himself to look at the photo. Joseph was afraid he might discover he’d never existed, either.

Albert took a breath. “Is that what you really think? That none of it matters?”

“Yes!”

“But what about your books, Joseph? I saw the collection you brought with you from school. Your suitcase was filled with stories. I saw Charles Dickens, and Roald Dahl, and Madeline L’Engle. I know you love stories. Do you think they don’t matter?”

Albert is overlooking an important distinction here: Dickens and Dahl, et al., drew a line marked by the severe square edges of a book cover to separate fact from fiction. They borrowed from their own experience as every author does. And while writing the story they lived in it to some degree, as every author does. But they were not the story. (It’s the same way that God, in the Bible, forms and upholds creation but is not creation.) Albert Nightingale–and the “real” Billy Marvel, who was not an 18th-century stowaway–wove the Marvel family chronicles from their own life and the objects and places they loved. And then they lived in it. It was their joy in life and solace in death. It was tru-er than true.

Joseph comes to accept this, but he was right the first time: stories matter as illustration, model, and illumination of truth, not as truth itself. When we value our narratives over the facts on the ground, there’s going to be trouble. The Marvels may be Selznek’s most personal novel, with the longest author note explaining how he got the seminal idea. There was a real, or perhaps I should say an actual “Uncle Albert”: Dennis Severn, an American-born Brit-by-choice and “artist of perverse genius who created a three-dimension historical novel out of bricks and mortar and timber and the objects he picked up for a song on countless stalls.” He decorated each room in period style and rented them out for travelers, but “visitors who giggled or who were otherwise unable to enter into the spirit of the enterprise would be summarily ejected” (quoted excerpts are from The Guardian obituary).

The author identifies with Joseph’s story—he literally writes himself in it, or rather draws himself. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that grown-up Joseph, as depicted in the last few pages, looks a lot like Brian Selznek.

For all their artistry and emotive appeal, Selznek’s stories lack something: a certain meatiness, or weight. Perhaps what they’re lacking is the ring of truth.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

4 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Really interesting stuff here, Janie. Now I REALLY want to read The Marvels…

This is fascinating. I would like to read The Marvels also!

I loved Selznick’s first two books, and was encouraging my children to read this one also, until I read it myself. On a web site promoting Christian children’s book reviews, it might be important to point out that what starts out as an innocent, kid-friendly story about ships and theaters turns into a story about homosexual lovers who are dying of aids. Uncle Albert rejoices over coming to to this part of London, since that his where he met his male companion. The two men are praised for doing such a good job raising a young boy. Christian parents and kids should beware of these messages.

Of course you are right, Peter–There are not one but two same-sex couples in the story. There’s Uncle Albert and Billy, and Joseph himself turns out to be gay, and the “best mate” he’s looking for when he arrives in London eventually becomes his life partner. I wanted to emphasize the made-up story angle of the book because I see that as the biggest problem. If we’re free to make up and live within our own narratives, then literally anything goes, and everything is okay. That’s the root issue, though I should have mentioned the homosexual angle.