In honor of the holiday this week that celebrates spooks and skeletons, here’s a post from a few years ago.

Everybody has their favorite C. S. Lewis quotes. Here’s one of mine: “Almost the whole of Christian theology could perhaps be deduced from the two facts (a) That men make coarse jokes, and (b) That they feel the dead to be uncanny.” And why is that, Mr. Lewis? Both human phenomena indicate an uneasy disconnect between body and soul, as though we humans were profoundly uncomfortable with being human. We find sex funny because it associates us with animals, even though we know we’re something more, and we find death uncanny because we perceive on some level that we’re not made to die:

It is idle to say that we dislike corpses because we are afraid of ghosts. You might say with equal truth that we fear ghosts because we dislike corpses–for the ghost owes much of its horror to the associated ideas of pallor, decay, coffins, shrouds, and worms. In reality we hate the division which makes possible the conception of either corpse or ghost. Because the thing ought not to be divided, each of the halves into which it falls by division is detestable.

I think there’s a lot of truth in this, but it doesn’t quite account for the human fascination with death, exemplified in slasher movies, haunted houses, and horror fiction. Death is the subtext of these Halloween thrills and chills, often with a supernatural twist thrown in, like the electrocuted psycho rising from the grave or the devil inhabiting a cute child’s toy (and giving it wicked eyebrows). Whatever we fear fascinates us, but the fear generated by that first plunge in a roller coaster or the sight of a full-grown grizzly on the other side of the campfire is not the same as that inspired by a ghost or a zombie—neither of which are “real” in any scientific sense.

I’m probably not the best one to account for the popularity of horror fiction and film, since I’m not remotely attracted to the genre. Walking Dead and True Blood are supposed to be great TV, but no thanks. Zombies and vampires have a very limited appeal for me—one-trick ponies. But just because I don’t like it doesn’t mean there’s no value in the genre, right?

Well. Not all scary stories are created equal. Ezekiel’s dreams and Daniel’s visions would shake the boots off us if we actually saw them, and fear is the usual consequence of humans meeting with God or angels. Often the fear intensifies, like the “great and dreadful darkness” that fell upon Abraham in Genesis 15:12. Some versions translate darkness as “terror,” and therein lies a clue.

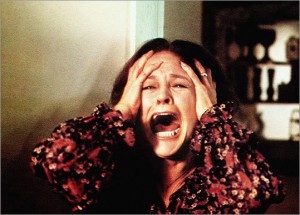

I make one main distinction in scare-lit, between terror and horror. These definitions are not water-tight, and exceptions abound. In general, though, horror literature includes one or more of the following: buckets of blood, mutilation of the human body, and an innocent victim (or victims). Think about the clueless nanny/bride/high school cheerleader who finds herself in the remote country estate/castle/basement where a horrible fate awaits her at the hands of a psychotic ex-wife/murderous husband/resurrected killer.

By contrast, terror literature 1) may involve blood but doesn’t rely on it; 2) usually includes a strong element of the supernatural, spiritual, or occult; and 3) features a victim who is fully or partially responsible. So “The Tell-Tale Heart,” Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, and The Portrait of Dorian Gray all qualify as terror stories. Leaning more toward horror are The Turn of the Screw, The Exorcist, and anything with “Scream” in the title. In general, I don’t consider horror stories to be of much value for Christians, for three reasons.

First, even though some horror stories rank as literature, the bargain-basement variety relies on shock therapy to deliver the goods. Creepy comics where a character screams “OMG!” every seven panels, or the “Goosebumps” novels that end every chapter with an unknown assailant grabbing a character in the dark, serve up scares like clockwork. In “Goosebumps,” the first horror series to be marketed to fourth-graders, these heart-stoppers usually turned out to be red herrings—the class clown playing a practical joke or the dreamer waking up. As the series went on it became more of a spoof than a scare, and the current Goosebumps movie mocks itself. But such regular jolts to the system, completely divorced from  character development or plot demands, are little more than cheap thrills. “At least they’re reading,” parents say; today R. L. Stine, tomorrow E. A. Poe. But the road between Stine and Poe isn’t straight. It may not even be a road. Poe makes demands: submersion in his early-gothic style, attention to character motivations, and adjusting oneself to the pace as it builds tension to a final payoff. Actual reading, in other words. Stine just sets up blocks of narrative to get in position for the next big scare.

character development or plot demands, are little more than cheap thrills. “At least they’re reading,” parents say; today R. L. Stine, tomorrow E. A. Poe. But the road between Stine and Poe isn’t straight. It may not even be a road. Poe makes demands: submersion in his early-gothic style, attention to character motivations, and adjusting oneself to the pace as it builds tension to a final payoff. Actual reading, in other words. Stine just sets up blocks of narrative to get in position for the next big scare.

But don’t all genres have their high-end and bargain-basement levels? Sure, but horror can become addictive in a way that other genres don’t: “a crude tool of physical stimulation, wholly devoid of mental, emotional, or spiritual engagement,” wrote Diana West in The Weekly Standard. She added, “Does that sound like a working definition of pornography?”

Second, horror usually scores its strongest impact from mutilating the human body. I’ve known of church youth leaders who hold Nightmare-on-Elm-Street marathons every Halloween for the teens. Harmless fun, they say. But what about the disrespect—if not contempt—for the human body that slasher movies express by carving it up every imaginable way? (Damages are likely to be worse in proportion to the victim’s attractiveness, though nerds and geeks come in for their share too.) “Fearfully and wonderfully made” applies to our bodies as well as our souls. If watching or imagining the desecration of God’s work is an actual pleasure, that may be cause for concern. This is sometimes justified as cathartic release: dramatizing our deepest fears in order to drain the potency from them. But if that’s true, why do horror movies have such a devoted following? Who needs to be “drained” on a regular basis?

Even though most parents agree that children younger than twelve or so shouldn’t be subjected to R-rated horror movies, they’re conflicted about horror literature–such as the Fear Street series for young teens, also written by R. L. Stine. Unlike Goosebumps, Fear Street gives kids something to be really scared about: several incidents of gruesome demise per volume. Both series declined with the rise of Harry Potter—

Even though most parents agree that children younger than twelve or so shouldn’t be subjected to R-rated horror movies, they’re conflicted about horror literature–such as the Fear Street series for young teens, also written by R. L. Stine. Unlike Goosebumps, Fear Street gives kids something to be really scared about: several incidents of gruesome demise per volume. Both series declined with the rise of Harry Potter—

But they’re baaaack. R.L. Stine and his writing stable have launched other series in the last few years, such as Goosebumps 2000, Classic Goosebumps, Fear Street Cheerleaders (why is there anybody left on Fear Street?), and Goosebumps Hall of Horrors. Some of these are a little less formulaic and frequently include knowing winks and dashes of humor. But the scares still come with the regularity of a city bus and little concern for plot, setting, and character.

Third, horror literature is obsessed with death. That’s the central fear, but also the central fascination—the glamour, if I can go that far. A proper Christian response to death is a necessary paradox: death is universal, but also, in the deepest sense, unnatural and ugly. We were not made to die. We earned that punishment by disobedience. Under the old law, touching a corpse made one unclean; if you were a priest, it made you ineligible to serve. Corpses were an abomination, the opposite of holiness. “Those who hate God love death” (Prov. 8:36). God did not allow that state of affairs to stand; Christ has conquered death for us, but at unimaginable cost to Himself. To play with it, tease it, flirt with it, curl up with it lurking between the covers strikes me as unhealthy at best.

None of this means that it’s a sin to read a Goosebumps novel or watch an occasional scary movie. And the horror genre does include a few worthy examples. But on balance I think terror literature (as I defined it above) has earned its distinction and is far more worthwhile to read. As I will try to prove tomorrow . . .

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

3 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thanks, Janie. I’m in the midst of trying to sort all of this out as I read about 150 middle grade fantasy/science fiction books for the Cybils awards. The books run the gamut from terror to horror to high fantasy to sci/fi to dystopia—you name it. The common factor is that there’s some kind of “fantastical” element. I know I like Poe, and feel as if the Poe-ish kinds of ghost stories can be of some value to read, but I can’t quite articulate why I think so. Looking forward to reading your further thoughts.

Processing….lots to think about here, Janie. Thanks.

When I was in high school, I read half of Stephen King’s It and realized this genre was not for me. I’ve not picked up another of its type since. While neither of my boys are drawn to scary stuff, I’m bookmarking this for the future in case their reading preferences take a turn. I appreciate the thoughtful points you’ve given us to consider.

Thank you for this!