The main problem with Christian fantasy may be, what do you do with Christ?

Honestly: can it be “Christian” without him? But it’s not easy to represent him without tipping the story into dogma, propaganda, or even heresy. His character in the gospel is indelible, and yet elusive; even when he can be located, chronicled, and quoted, he’s hard to pin down. “Nobody ever spoke like this man,” said the hapless temple officers who were sent to arrest him (John 7:46). “Who are you?” his bewildered contemporaries asked, from a blind man to a Roman governor. A compassionate shepherd who speaks of hellfire, a lawkeeper who seems to waive the law, a king who serves, an immortal being who dies–it’s no wonder they misunderstood him then, and we barely understand him now. Something about him eludes us, and any attempt to represent him outside Scripture is bound to fail.

Honestly: can it be “Christian” without him? But it’s not easy to represent him without tipping the story into dogma, propaganda, or even heresy. His character in the gospel is indelible, and yet elusive; even when he can be located, chronicled, and quoted, he’s hard to pin down. “Nobody ever spoke like this man,” said the hapless temple officers who were sent to arrest him (John 7:46). “Who are you?” his bewildered contemporaries asked, from a blind man to a Roman governor. A compassionate shepherd who speaks of hellfire, a lawkeeper who seems to waive the law, a king who serves, an immortal being who dies–it’s no wonder they misunderstood him then, and we barely understand him now. Something about him eludes us, and any attempt to represent him outside Scripture is bound to fail.

This includes the figure of Aslan. I’ve never felt entirely comfortable with it, and these are just my thoughts, not intnded to bind the conscience of anyone else. I’m not saying it’s a mistake, much less a sin, to represent Christ as a lion. But I am saying it’s inadequate, not matter how awesome the lion. Lewis was very much opposed to an animated movie version of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe when it was first proposed to him: “Aslan is a divine figure, and anything remotely approaching the comic (anything in the Disney line) would be to me simple blasphemy.”

If I were the correspondent he was addressing in that letter, I might (though probably not) have been bold enough to write back: “But you started it!” It was Lewis who presented the Son of Man as an animal in the first place. It’s not blasphemy, but is it effective? And with our reliable human capacity for getting things wrong, might some Narnia enthusiast prefer to picture Jesus as Aslan when she prays? (Just as some devotees of The Shack might prefer to picture God as a rotund black woman?) Lewis seems to recognize that possibility when Aslan says to Lucy, at the end of Dawn Treader (both book and movie), “In your world you must come to know me by another name.”

But that’s just it: he has no other name. “There is no other name given under heaven and earth whereby we may be saved” (Acts 4:12). Yes, I know: the name and the character of Aslan are figurative. I understand figurative. But the figure can only suggest the reality, and should never be substituted for it. His name is Jesus: Jehovah saves.

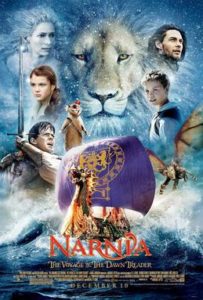

With that in mind, let me state briefly what I thought of the movie version of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. (And I’m only getting around to it now because I’m too much of a tightwad to attend very many first-run movies in the theater.)

I thought it was pretty good. Many of my Christian friends were disappointed because it differed from the book in so many ways: by manufacturing a rivalry between Caspian and Edmund and making Lucy jealous of her sister Susan, and especially by shoehorning the White Witch into the story, with the mysterious green mist that appeared at every turning point of the voyage. (Lewis might have thought the same, given his opinion of the movie version of King Solomon’s Mines, which included “a totally irrelevant young woman in shorts who accompanied the adventurers wherever they went”). And what was up with those seven swords?

But visual storytelling is different from verbal, and has different requirements. The original story lacks some elements that are deemed essential for a movie epic, such as a clear villain and a strong central conflict. Whether a movie would have succeeded commercially as a straight re-telling of the book is doubtful. (Though I was among the many disappointed with the movie version of Prince Caspian, that book had some of the same problems and wouldn’t have survived a strict screen interpretation.)

So there should be a stronger unifying theme to all the adventures, and the movie is straightforward about what it is: each character will have to face some sort of temptation in order to complete the mission. In the book, Eustace is the central temptee, with Caspian as a secondary statement of that theme (i.e., his sinful desire at the end to forsake his calling and continue on to Aslan’s country; in the movie that’s his desire from the beginning). Eustace’s redemption is central to the movie version as well, but that theme is supported by echoes in the lives of the other characters–all are tempted, and all have to overcome. The Eustace story was made even stronger than it is in the book by giving the dragon more to do, like pulling the Dawn Treader out of the doldrums and charging in to fight the serpent of the Dark Island. Even if somewhat cliched, this is still good cinema storytelling.

Reinstalling the White Witch as the villain is less successful, precisely because the creators of the movie were reluctant to stray to far from the original plot. That whole storyline is muddled–is she sending the green mist or is she part of the green mist, subject to some greater malevolent power? The Lone Island slave trade is meant to supply victims for her, but it’s not known what she wants them for or why they are held in limbo until the power of the seven swords* sets them free, and the little subplot of the family divided by slavery feels tacked-on.

But I liked The Voyage of the Dawn Treader more than not, and two scenes (or shots) I loved. They would be impossible to portray in a book, and give us some idea of why moving pictures are a legitimate art form. In one, the dragon Eustace is asleep on the beach. He opens one eye, and reflected in it is the figure of a lion approaching. It lasts only a second, but that’s long enough to catch a glimpse of the power of Christ encircling a single life and changing it forever.

In the other scene, the voyagers have reached the end of their world and are walking toward the wall of water that marks Aslan’s country. We see their shadows on the sand, and then the shadow following them: a lion. It’s a beautiful image of the Lord ordering our steps and finishing his work, even when we haven’t a clue what it is.

When the lion himself appears, and Liam Neeson’s voice comes out of his mouth, it’s an anticlimax. No offense to Neeson–no human voice would have sufficed. Lewis tried, and his stepson Douglas Gresham and the creators of the movie tried, but Aslan’s actual appearance is always going to be an anticlimax. Only Jesus can adequately fill the Christ-figure role, and there will always be something about Him that we can’t communicate in art. I think that “something” may be holiness, which is impossible for an unbeliever to understand (and can we say that we believers fully understand it?). It can only be suggested: as a glory that has departed, as a light whereby we see everything else. It’s a shadow on the beach, a reflection in a dragon’s eye. Someday “we shall see him as he is” but now we journey by faith. And faith always includes something that eludes us.

*I’m working on a theory that the seven swords bear some relation to the seven spirits of the churches, which will have to speak in unity before the Lord returns, but haven’t got too far with it yet. In fact, it probably stops right here.

See True Grit and True Grace and Jane! Jane! for more movie excursions. As for where Christ fits, in literature and by extension in the movies, Emily has begun a discussion of that here.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

4 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hi Janie,

Agreed! The Narnia books are teeming with themes – how to choose just one for a 2 hour movie? I love Reepicheep for his nobility and the Eustace for his downright humanness. Warts, dragon skin, and all!

Have you had a chance to read Planet Narnia yet? I hate to give it away if you haven’t…. but much of that imagery was present in the movie.

Blessings,

Renee

(P.S. – Thanks for fixing the apostrophe!)

Hi Janie,

Agreed! The Narnia books are teeming with themes – how to choose just one for a 2 hour movie? I love Reepicheep for his nobility and the Eustace for his downright humanness. Warts, dragon skin, and all!

Have you had a chance to read Planet Narnia yet? I hate to give it away if you haven’t…. but much of that imagery was present in the movie.

Blessings,

Renee

(P.S. – Thanks for fixing the apostrophe!)

As your friend-in-cheapness, I am now eagerly awaiting my Netflix DVD of this film!

I think Lewis was right to attempt to portray the divine. But I think you’re right–there is always a cost involved, something lost in the figure.

As your friend-in-cheapness, I am now eagerly awaiting my Netflix DVD of this film!

I think Lewis was right to attempt to portray the divine. But I think you’re right–there is always a cost involved, something lost in the figure.