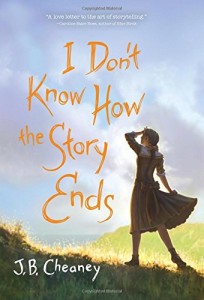

Janie’s newest novel for young folks, I Don’t Know How the Story Ends, hit store shelves this month, and she’s been busy signing copies and enjoying early reviews. Book babies are a bit like eggs in a nest: patiently, the author sits on the drafts of the book, keeping them warm until they hatch. Publication day is a bit like the fledgling leaving the nest: will it fly? Will it survive?

Janie’s newest novel for young folks, I Don’t Know How the Story Ends, hit store shelves this month, and she’s been busy signing copies and enjoying early reviews. Book babies are a bit like eggs in a nest: patiently, the author sits on the drafts of the book, keeping them warm until they hatch. Publication day is a bit like the fledgling leaving the nest: will it fly? Will it survive?

I read an advance copy of the book (it’s wonderful), and I took the opportunity to ask Janie a few questions about this story. Even if you haven’t read the book yet, the interview questions below will be of interest as we discuss some broader concepts such as research for historical novels, the writing process, and the great function of art!

Janie, your previous historical fiction novels were set in familiar time periods: The Playmaker and The True Prince in Elizabethan England and My Friend the Enemy in the 1940s American Northwest. The time period for I Don’t Know How the Story Ends (IDK) is a less familiar time period (early Hollywood during WWI; think: Charlie Chaplin film era). How do you start researching the smaller details of a time period: the vocabulary, sayings, cultural references known at that time, makes and models of cars, and so forth? Did IDK take more research in these areas than your other historical fiction novels?

I used to go to the library and browse the titles in a certain Dewey range, but now I go to the Internet and start clicking around–then I go to the library and browse the titles in a certain Dewey range. General books on a subject can often direct you to more specific books on the subject if you make use of the footnotes and bibliography. Internet research is always chancy because anybody can post anything, but the greatest benefit of Internet research is providing personal contacts. For my Shakespeare novels, I subscribed to an email list of academics, actors, and enthusiasts that was almost too much information. For My Friend the Enemy, I contacted the curator of the local historical museum who was able to connect me to local historians (i.e., old guys). I did basically the same thing on a larger scale with IDK.

I used to go to the library and browse the titles in a certain Dewey range, but now I go to the Internet and start clicking around–then I go to the library and browse the titles in a certain Dewey range. General books on a subject can often direct you to more specific books on the subject if you make use of the footnotes and bibliography. Internet research is always chancy because anybody can post anything, but the greatest benefit of Internet research is providing personal contacts. For my Shakespeare novels, I subscribed to an email list of academics, actors, and enthusiasts that was almost too much information. For My Friend the Enemy, I contacted the curator of the local historical museum who was able to connect me to local historians (i.e., old guys). I did basically the same thing on a larger scale with IDK.

So, you’re telling us that the skills we high school research teachers teach are important! Janie, you and I have had several discussions on this next issue, but for our readers’ benefit, walk us through the process of “allowing” a character to use language you personally don’t use and might even find offensive. (For you readers, there is one “damn,” one “bat’s chance in hell” in the book).

There’s usually no good reason to use a curse word in a children’s book. The reason I do so here is to say something about the character and the character’s state of mind. We’ve already established that kids don’t generally talk this way in this period (the same character has used innocuous slang terms thus far, and as soon as he says the curse word, another character corrects him). To my mind, the exchange becomes a little lesson in proper decorum–but maybe that’s just wishful thinking on my part! The use of “hell” is actually a misquote, or mixing of common metaphors, which the same character (Ranger) does another time or two in the narrative. Kind of a quirk, and it allows for a semi-humorous reply from Isobel.

There’s usually no good reason to use a curse word in a children’s book. The reason I do so here is to say something about the character and the character’s state of mind. We’ve already established that kids don’t generally talk this way in this period (the same character has used innocuous slang terms thus far, and as soon as he says the curse word, another character corrects him). To my mind, the exchange becomes a little lesson in proper decorum–but maybe that’s just wishful thinking on my part! The use of “hell” is actually a misquote, or mixing of common metaphors, which the same character (Ranger) does another time or two in the narrative. Kind of a quirk, and it allows for a semi-humorous reply from Isobel.

Good explanation. We look at just those sorts of background issues when we evaluate a book on this site! If I were assigning students an essay topic on this book, I’d use the following quotations from the book itself, both spoken by this same character we just discussed (Ranger):

“This is about art…and life and truth and beauty too, if we can pull it off.” and “…the story just went somewhere else. I couldn’t argue with it. It was one of those times when you feel like you’re part of something bigger, and you just have to go along.”

How well do these quotations reflect your own writing aspirations and practice? Can you elaborate on how these quotations might both reflect the book’s storyline and theme but also reflect your own beliefs about art in general?

You have definitely picked out two key thematic statements.

Christians are artists and works of art, living out God’s story. We get excited about self-expression because we have a self to express. That’s what excites Ranger so much: a brand new art form that incorporates story, motion, emotion–and special effects! But he wants to do more than just “express himself.” He senses that there’s something bigger behind every artistic enterprise (“truth and beauty”). I usually find, when I’m well into the first draft of a novel, that I have to “let the story go” because it wasn’t really about what I thought. It’s bigger than me, and craft becomes art when it surrenders itself to something bigger.

What a great statement about art and craft! And now, let me ask you about that title: when did you know how the story would end, especially as regards Isobel’s father? Did you have the ending in mind from the beginning of the writing process? Or did you change your mind as much as Isobel, Ranger, and Sam re-worked their ending?

As in most, if not all of my novels, I had a general idea about the end from the beginning. How to get there is the question–and the trouble, while I’m writing a first draft–and the details of the story will certainly shade the ending. I knew Isobel’s father would return [from the war], and it wouldn’t be a happy occasion. One significant feature that changed as I was re-working the last few chapters came from my editor. There wasn’t much of Father in the original manuscript I submitted: he was a spiritual presence over the action, but not so much a physical presence. I suspect that I was as conflicted about him as Isobel. My editor said we needed to see more of him, and after some initial resistance, I gave in. So I changed my mind, or rather she changed it for me. Editors are usually right.

Thanks, Janie!

Readers: Now it’s your turn! Go find a copy of I Don’t Know How the Story Ends, read it, and shoot us a question in the comments.

all images from pixabay unless otherwise noted; book cover image from amazon; author picture from author

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Janie’s words about the story going someplace of it’s own accord remind me of the way Tolkien spoke of his characters in LOTR.

Yes!