If you have a chance to catch a Shakespeare play performed on a real stage with live actors, DO IT! That’s what he wrote the plays for: performance. Unfortunately theater tickets are expensive and amateur performances (like you might see at a local college) are sometimes . . . well . . . amateur. But Shakespeare well done is a thrill, even if you don’t catch what’s going on every minute. While waiting for the next Shakespeare touring company to present Romeo and Juliet in your town, the local library or video store may have some of the filmed versions of popular plays. Here’s what you might see if you check them out.

As You Like It (2006), directed by Kenneth Branaugh. This is the only Shakespeare film directed by Branaugh that he did not also appear in. As a setting he decided on an English colony in 18th century Japan–for no particular reason, I guess, except it interested him. I’ve seen it, and recall no objectionable elements in it, but no memorable ones either.

Hamlet (1990). Franco Zeffirelli directs, and Mel Gibson plays the melancholy Dane like he’s not entirely pretending to be insane–Lethal Weapon fans will see shades of Martin Riggs in his performance. But I call this a good “all purpose” version of the play. Mel’s Hamlet strikes you as somebody who might have turned out okay if his mother hadn’t remarried so soon after his dad died–he’s already upset about that, but then the ghost appears and everything gets rotten in Denmark really fast. Paul Scofield makes a great ghost, Glenn Close is a sensuous and oddly girlish queen and Alan Bates is a hearty king eventually hoist on his own petard. Helena Bonham-Carter’s Ophelia seems a bit too spunky for the type of girl who goes mad when things get rough, but her madness is touching, anyway.

Hamlet (1997) Kenneth Branaugh directed and starred in this version that breaks with tradition in several ways. For one thing, it’s uncut, and therefore runs to almost four hours! Before settling in with a really big bowl of popcorn to watch it, I’d recommend reading a good synopsis first, so you’ll understand who is this Fortinbras character who keeps popping up. Some scenes (like the “To be or not to be” soliloquy) are outstanding, some are over the top (like the ghost’s appearance amid hellfire and brimstone), some go on a little too long (like the duel, in which Hamlet and Laertes chase each other all over the palace). The movie, ultimately, goes on a little too long as well, but it makes an interesting contrast with the 1990 version–notice especially the use of light. This version also includes a couple of nude bedroom scenes that I don’t think Shakespeare had in mind when he wrote the play.

Hamlet (1999), directed by Michael Alymeyda. Ethan Hawke plays the title role in a modern-day setting that pictures Hamlet brooding over his uncle’s takeover of Denmark Corporation. Image trumps word in this version: photos, video clips, televised interviews, closed circuit TV, news broadcasts, stock price crawlers, mirrors, computer monitors, fax machines. Both Hamlet and Ophelia are amateur photographers, and he’s an obsessive film editor. Both are alienated from their parents, their society, and eventually each other. No wonder: all the characters are so surrounded by multi-media that reacting to each other as human beings is impossible. Which may be the point: Hamlet’s inability to act is due to a society that blurs the distinction between image and reality. Or something like that. This is more Alymeyda than Shakespeare, but it’s interesting.

Henry IV, Parts one and two. Don’t look for it under that title, but rather Chimes at Midnight (1965), directed by Orson Welles, who stars as Falstaff. Probably Welles’ finest acting role, and often ranked among the best Shakespeare movies ever. Since two plays are compressed into one 2-hour film, much is left out, but it’s a good representation of Falstaff’s rowdy spirit. Expect some tavern scenes featuring prostitutes.

Henry V (1989), directed by Kenneth Branaugh. This is the movie that brought Branaugh to worldwide attention (he also stars as Henry) and touched off a miniature Shakespeare boom. It’s helpful to have a little background in the historical setting, or the first few scenes may be puzzling. But stick with it–once it gets going, the movie gallops like a charging steed, and you almost have to clamp your jaw to keep from cheering at the St. Crispin’s Day speech. Shakespeare probably wrote the play in a spirit of gung-ho patriotism, and an earlier movie version (1945) directed by Laurence Olivier captures that spirit. But Branaugh’s version draws out the darker elements. He grandstands a bit over a pile of corpses on the battlefield (Please! Cut away from the heroic pose!), but redeems himself in the courtship scene with Princess Katharine that follows directly after. Quick note about the Olivier version: If you have a chance, get it for the first scene, which depicts the play as it might have debuted at the Globe theater. We see rowdy audience members, actors backstage checking over their lines, young boy apprentices dressed as women, and finally Olivier himself clearing his throat as he gets ready to make his entrance. After the first scene, the play shifts to a historical context with a historical king, but the glimpse into 16th-century theater life is fascinating.

Julius Caesar (1971), directed by John Gielgud. This one might be hard to find, but I include it because it’s the most recent movie version of JC that I know of. The cast is made up mostly of Americans who were better known at that time than now. Jason Robards as Brutus seems to be sleepwalking through his performance, and since Brutus is the hero of the play, this is a large problem. Charleton Heston is a convincing Antony and Gielgud, grand old man of the British stage even then, appears as Caesar. There’s an older version (1953) with Marlon Brando as Antony and Gielgud as Brutus, which has some fine moments.

Love’s Labor’s Lost (2000), Directed by Kenneth Branaugh, who stars as Berone. Branaugh’s inspiration was to stage this play, one of Shakespeare’s earliest, as a 1930s musical–complete with classic love songs by Gershwin and Porter, fluffy costumes, lovestruck young men dancing on air, slapstick comedy, even a water ballet. All I can say is, it must have seemed like a good idea at the time . . . At the end, I suspect more viewers than not were wondering, “And what was that all about?”

Macbeth (1971), directed by Roman Polanski. Jon Finch is Macbeth. I haven’t seen it, but it’s supposed to be extremely violent (define “extremely”). Orson Welles directed and starred in an earlier Macbeth, (1948). I haven’t seen that one either.

The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021), directed by Joel Coen, one-half of the Coen brothers. Denzel Washington stars in the title role with Frances McDormand as his nagging wife. Very atmospheric in black and white. But I haven’t seen it–yet.

The Merchant of Venice (2005). Directed by Michael Radford, with Al Pacino, Jeremy Irons, and Joseph Fiennes. The story of a beautiful heiress, the man who loves her, a miserly Jew, and the man who owes him, never looked so lush. Or so watery, but that’s Venice for you. In a collection of good performances Jeremy Irons stands out as the Merchant, Antonio, who is willing to “risk and hazard all he hath” for the sake of friendship. The movie is worth watching just for the trial scene, which is as dramatic a presentation of grace vs. law as I’ve ever seen. But contemporary directors seem more interested in showing how Shylock is debased and brought down by mean Christians, and Mr. Radford is no exception. Shylock’s daughter Jessica, who converts for love, is depicted as regretting her choice at the end, though the play itself indicates no such thing. Still the movie would be good family viewing except for several scenes of Venetian ladies (of the night) strolling the streets with bosoms uncovered. This kind of thing was not unknown for the time, or so I’ve read, but I doubt that a passion for historical accuracy is what drove the filmmakers.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2000). Kevin Klein (Bottom), Rupert Everett (Oberon), Michelle Pfeiffer (Titania), Calista Flockhart (Helena), Christian Bale (Demetrius) and on and on–a starry cast that doesn’t quite mesh. MND is a light and bubbly play, but moments that should be magical come down a little flat-footed in this version. There are a few touching moments, and my favorite comes in a scene that’s usually anything but touching. It comes when Flute the bellows-mender, playing “Thisbe” in that terrible play before the Duke, pulls off his ridiculous wig and speaks the lines with so much conviction that everyone has stop laughing. He saves the play and, for me, the movie. Watch out for one scene where the four lovers are discovered by Duke Theseus after their night of wild confusion; they’re mostly or entirely undressed. (Classic movie fans may want to check out the 1935 black and white version of MND, for historical interest only. The best thing about it is James Cagney as Bottom; the worst thing is Mickey Rooney, whose Puck appears to have escaped from a mental institution.)

Much Ado About Nothing (1993). Kenneth Branaugh again, both directing and starring as Benedick. The story is exuberantly told in an Italian setting bathed in Mediterranean light. It’s one of Shakespeare’s great romantic comedies, and it’s played as a comedy, with broad touches. You may wonder why everyone strips off their clothes to take a bath in the first scene, and what IS all that with Dogberry and his imaginary horses. The play itself has its problems–I always thought Claudio was a hyper-jealous jerk and saw no reason for Hero to take him back. But the movie almost makes it work, and makes some nice, old-fashioned statements about love and marriage too.

Much Ado about Nothing (2012). Directed by Joss Whedon, perhaps best known for his creation of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and the short-lived Firefly series. The play was filmed in one weekend at his Santa Monica mansion, with actors who were also friends and co-conspirators. The result is entertaining and professionally done. The setting is contemporary and it’s implied that Benedick and Beatrice were much more involved in the past. Nathan Fillion’s Dogberry is less over the top than Michael Keaton’s, and funnier too.

Othello (1995), directed by Oliver Parker. Laurence Fishburne is Othello, with Kenneth Branaugh as a mesmerizing Iago. Moody, dark and intense–but this is tragedy, after all. Othello is usually portrayed as an honorable man with a fatal flaw, and Fishburne adds a touch of borderline epilepsy that helps explain his jealous rages. In this version, Iago feels a homoerotic attraction for the Moor, which helps explain . . . well, you decide. For the most part, this is a gripping production.

Richard III (1995), directed by Richard Loncraine. Ian McKellan (you know–Gandalf) plays the king with the worst reputation in British history. Warning I: Shakespeare may have done a hatchet job on Richard’s personality–it’s never been established beyond doubt that he murdered the little princes in the tower. Warning II: this is a shocking and violent film, but it’s a shocking and violent play, too. The main problem with Richard III these days is that it’s hard to keep all the characters and politics straight. It takes place at the end of the Wars of the Roses, which I still haven’t figured out. The bottom line: Richard wants to be king and will play any part and back-stab any relative to get there. This production updates the setting to an alternate-history Fascist takeover of England in the 1930s.

Romeo and Juliet (1968), directed by Franco Zeffirelli. This is a lush, Renaissance-era production notable for its use of teenage actors to play the leads. (Before that, it was more common to have the star-crossed lovers portrayed by adults). It’s all very romantic, but a little too romantic for me. Shakespeare’s point, I believe, was that these kids were in love with love and their youthful passion, running contrary to the other passionate hotheads in Verona, led to tragedy. Still, it’s a beautiful production and well-acted (one scene features Romeo’s bare backside as he wakes up after his wedding night. You will need it to balance

Romeo + Juliet (1997), directed by Baz Luhrman. Leo diCaprio and Claire Danes are the star-crossed lovers in a story updated to the present time and set in Verona Beach, California. The Montague and Capulet gangs blaze away at each other with oversize sidearms (favorite line: “Put down your swords!”) to a heavy metal soundtrack, while Mercutio poses in drag and Romeo and Juliet play their balcony scene in a swimming pool. Some scenes are nice; others strike me as way overdone. Like Alymeyda’s Hamlet, it seems more like upstaging Shakespeare than working with him.

The Taming of the Shrew (1967), directed by Franco Zefferelli. Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor chew up the scenery as the feuding lovers Petruchio and Kate. There’s too much time given over to Kate’s yelling and Pete’s chortling in his beard–I would have liked more dialogue. But it’s fun, and the concluding scene is played straightforwardly. Sort of. Kate sounds sincere when she pledges loyalty and obedience to her lord, but you have the idea she’ll know how to get what she wants from him. An even better production, in my view, is the 1980 BBC version with John Cleese as Petruchio. The actors play it straight with no modern reinterpretation–this Kate needs to be tamed. And her suitor is a little rough around the edges, too. This version of the play ends with the principal characters, neatly matched up, singing a madrigal version of Psalm 127 around the dinner table.

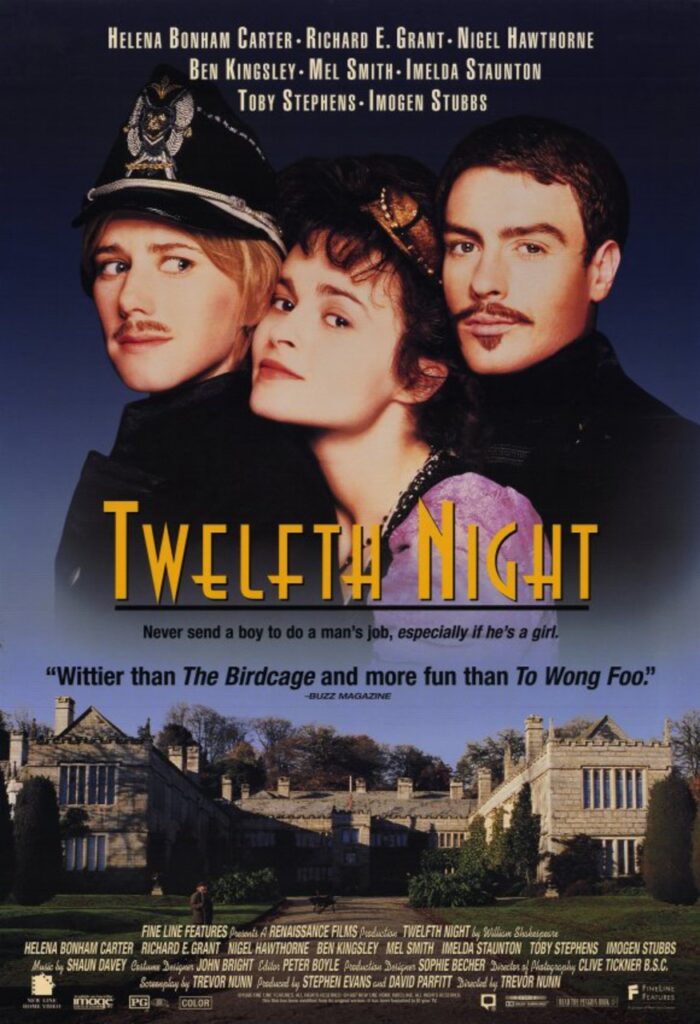

Twelfth Night (1996), directed by Trevor Nunn. This is an enchanting production of an enchanting play, though newcomers to Shakespeare may have a hard time suspending their disbelief at first. But deal with it: just accept that Viola can be easily confused with her twin brother Sebastian, Olivia can fall in love with a girl whom she believes is a boy, and Orsino can switch his affections from Olivia to Viola at the drop of a soldier’s cap. Love is crazy, Shakespeare can be saying–who can figure it out? And who would want to?

An Oscar-winning film about Shakespeare and Elizabethan times may find its way into Eng. Lit. classrooms, but in my opinion it shouldn’t.

Shakespeare in Love (1998). A true history of young Will–NOT. Parts of this story are factual, but most of it bears no relation to the facts. Though an interesting idea, and very funny in places, Shakespeare in Love can’t make up its mind what kind of movie it is. It begins as an offbeat comedy with shades of Money Python, veers into bedroom farce, then shuttles between steamy romance and serious drama. Watching the first-ever performance of Romeo and Juliet come together against the background of “real” events is the best part, but the climax of the movie slides into the pattern of every feel-good ending since Rocky. Everyone, even the Puritan nay-sayer, is on his feet and applauding wildly at the end of the performance, while confetti rains from the sky and the Queen herself makes a surprise appearance. According to the story line, Shakespeare writes the play in order to prove that he can successfully portray the nature of true love on stage. But Romeo and Juliet doesn’t portray the nature of TRUE love at all, and I doubt that the real Shakespeare intended it to. What the play shows is the power of sexual attraction, which might have grown into true love if it had the chance. It didn’t have the chance, and that’s why R&J is a tragedy. The main plot of Shakespeare in Love likewise confuses sex and love, and they’re not the same. (Trust me on this.)

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.