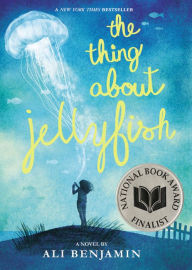

Betsy and Janie are continuing their discussion of possible 2016 Newbery Award winners. On deck today is a novel by a debut author which has already been honored as a National Book Award finalist.

Janie: I heard someone mention lately that most of the children’s books getting the rave  reviews this year seem to be downers—oh wait, that was you! Well, here’s another one, though I’ll admit it tried hard to end on a hopeful note. Suzy Swanson, our protagonist, has been known as a nerd for most of her school career. Franny is her one friend, but after the girls start middle school Franny undergoes a transformation: for the first time, she wants to be more like the cool kids. Suzy can’t, or won’t, transition along with her, so the two friends drift apart during sixth grade. As she’s about to start seventh grade, Suzy hears the worst news she could possibly imagine: Franny has drowned while on a beach vacation. Why?? It doesn’t make any sense, and to make things worse, Suzy and Franny did not part on friendly terms when they last saw each other—just the opposite.

reviews this year seem to be downers—oh wait, that was you! Well, here’s another one, though I’ll admit it tried hard to end on a hopeful note. Suzy Swanson, our protagonist, has been known as a nerd for most of her school career. Franny is her one friend, but after the girls start middle school Franny undergoes a transformation: for the first time, she wants to be more like the cool kids. Suzy can’t, or won’t, transition along with her, so the two friends drift apart during sixth grade. As she’s about to start seventh grade, Suzy hears the worst news she could possibly imagine: Franny has drowned while on a beach vacation. Why?? It doesn’t make any sense, and to make things worse, Suzy and Franny did not part on friendly terms when they last saw each other—just the opposite.

The book is beautifully written with well-rounded characters (or at least the two main ones). It addresses, or touches on, big questions like Why are we here? and Why do we drift apart? and Why must we die? The problem, as I see it, is not in the questions but in the answers. Before we get into that, what positives did you see, Betsy?

Betsy: You’re right, Janie—I did say that there are a lot of books that are downers this year, and this one is no exception! This book was well crafted, and that makes it even more poignant. We, as readers, ache with Suzy and experience all her stages of grief over the death of her best friend. Her overwhelming need to understand the “why’s” you mention, her desperate attempts to do something about those questions, and her inability to reach out to the people she loves most are heartbreaking; I may have even shed a few tears. The flashbacks to Suzy and Franny’s happier, younger days are bittersweet. The framing of the story in light of the scientific method is clever and effective, helping the readers pace themselves with Suzy’s growing understanding. Often extended metaphors don’t work, but the jellyfish motif and the scientific method metaphor both add to this middle school coming-of-age story. I can certainly see why people resonate with it. I’ve heard someone say that we read literature for the questions it asks, not necessarily the answers it provides. Oh, wait—that was you! At any rate, this novel provides some fairly modern, disheartening answers to its questions. For instance, what does the image of the earth as dust mote mean to Suzy? What does she conclude is so special about humanity as compared with, say, jellyfish?

Janie: That’s a good question. The book opens with a “quote” from Suzy’s science teacher Mrs. Turton (who takes the role of wise mentor): “Science is the process for finding the explanations that no one else can give you.” Explanations, mind—not answers. The best we can do, apparently, is figure out the what’s and the how’s, but we’re on our own for the why’s. Even most scientists admit that you can’t logically get from “is” to “ought”—science has no framework for determining morality, only utility. Some of them argue that morality develops from a common framework based on the benefit to society at large. But as you say, if that’s the case what makes humans more special than jellyfish? Just because they can make the rules? That doesn’t seem fair. One thing about jellyfish that Suzy discovers is their durability: they’ve been here for eons, unchanging, while humans evolve and change and destroy. as the author describes her own study of the species, “It was sinking in [with me] what our species has done to our planet and by extension, ourselves. Grief is the only word to describe what I felt.”

And it’s a pretty bleak picture to present to kids. The author tries to get around the bleakness the same way Philip Pullman does in his atheistic children’s fantasy trilogy, His Dark Materials: with the semi-deification of “dust.” In medieval literature, “dust” was the fifth element, a link between the material and the spiritual. Toward the end of the novel, Suzy reflects that “Maybe instead of feeling like a mote of dust, we can remember that all the creatures on this Earth are made of stardust.” This is factually true, as everything in the universe is created from the same simple elements. But the author obviously means it to be taken in a quasi-spiritual sense—that somehow, we’re kin to the stars. Kind of a magical materialism, I guess. It’s almost as if humanity can’t quite shake the notion of some transcendent (i.e., spiritual) element that’s essential to human beings. In actual life, kids may take some comfort from this kind of thinking, but I doubt it will be much.

Click these links to see our discussions of Most Dangerous, The Nest, Gone Crazy in Alabama.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.