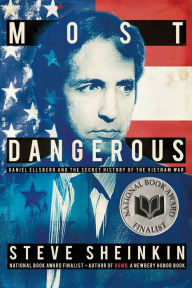

It’s that time again! Less than a month before the American Library Association announces their Youth Media Awards, and chief among them is the coveted Newbery medal. The speculation has begun, and for the next few weeks, Betsy and Janie are going to be talking about some of the leading contenders. Please note: our discussion does not indicate that we recommend all these books, but only that they have attracted a lot of attention and will soon be coming to a library near you (if they haven’t already). Today we’re gazing gimlet-eyed at Most Dangerous: Daniel Ellsberg and the Secret History of the Vietnam War by the prolific nonfiction writer Steve Sheinkin.

Betsy: Sheinkin has really distinguished himself these past few years as a name in middle grades level  nonfiction: his historical topics are interesting to start with (the Manhattan Project, Benedict Arnold), and he writes terrific narratives. Win-win for all kids who enjoy history in story format.

nonfiction: his historical topics are interesting to start with (the Manhattan Project, Benedict Arnold), and he writes terrific narratives. Win-win for all kids who enjoy history in story format.

His latest book, Most Dangerous, has garnered critical acclaim this fall, including a spot on the National Book Award for Young People shortlist. The subject is the Vietnam War, a subject my high school history classes rarely covered. I learned a lot from this book! His focal point is Daniel Ellsberg, a man who began the war working for the government and very much in favor of the war itself. By the end of the war, however, Ellsberg was one of its most outspoken and prominent critics. He is best known for the “Pentagon papers,” top-secret documents about the War that Ellsberg basically stole from the Defense Department and leaked to major newspapers. Janie, I know before you read it, you were musing over other possible “focal points.” Who else would have made a good subject for this time period? Do you think Sheinkin made a good choice in Ellsberg?

Janie: That’s an interesting question, Betsy. I think Ellsberg is a great choice. He represents the accepted view today, that involvement in Vietnam was a mistake and we needed to get out of the conflict by any means necessary. That period of history remains a flashpoint: every conflict the US engaged in (or will engage in) from that point on is likely to be viewed as a “potential quagmire like Vietnam.” As the first war we ever lost (preceded by Korea, the first war we never actually won) Vietnam led to a new era of distrust and cynicism that we have yet to overcome—and maybe never will. Ellsberg, as an avid war supporter who became its “most dangerous” critic, makes a fascinating study in contrasts within his own person.

I think Sheinkin handles the material in a fairly balanced manner, though obviously sympathetic to Ellsberg—who, we learn, is still an outspoken war critic! For a different point of view, it would be interesting to compare Chuck Colson’s account. Christians (those of us on the other side of sixty, that is) may remember that Colson, founder of Prison Fellowship, spent time in federal prison for something to do with the Watergate scandal. Actually, he was convicted and served time for obstructing justice in the Ellsberg investigation. Colson is only mentioned a few times in Most Dangerous, but he tells the story from his point of view in the early chapters of his autobiography, Born Again, and in the second chapter of The Good Life.

Betsy: Yes; Colson is a fascinating contrast to Ellsberg. Perhaps people could read Sheinkin’s book and compare/contrast it with Colson’s autobiography. I wasn’t alive during the Vietnam era, so I’m responding to the story through the lens of others’ insights but I thought Sheinkin’s treatment of the presidents was fairly well done. Aside from the language he felt the need to quote, it seemed that most of the presidents came off as—if not sympathetic characters—at least understandable characters. We may not agree with all of their decisions, and hindsight is always 20/20, but I do think they truly thought they were making the best possible decisions given the circumstances in which they found themselves. Sheinkin makes it clear that they felt like they were between a rock and a hard place. What do you think of his handling of our previous commanders-in-chief, particularly as we look to an election year and are in the middle of conflict overseas?

Janie: I think his treatment is fairly even-handed and reasonably sympathetic. I was alive during that time but wasn’t paying much attention, except when the war—and especially the draft—affected people I knew. I had heard of Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon papers, but was vague on the details—so I leaned a lot from this book, too. I was surprised to learn that some of the highest people in government, including presidents, who got us into that conflict didn’t think we could actually win it. There’s a lesson for future presidents: if you’re going to get into a fight, you’d better fight to win! Sheinkin sees an obvious parallel between Daniel Ellsberg and Edward Snowdon, who recently leaked intelligence documents about the U.S. surveillance program and had to seek refuge in Russia. Clearly the issue of government overreach and the people’s right to know is still with us, and it’s vital to know the history.

I have to mention one big caution. Sheinkin is rightly recognized as an incomparable writer of history for young people, and I admire the way he covers complex events while maintaining a sense of dramatic tension. In previous books, The Notorious Benedict Arnold and Bomb, he includes a small amount of profanity in the form of quotation—maybe two or three words. In Most Dangerous, he goes over the top with profanity and crude language, including just about everything except the f-bomb. It’s all quoted, and I’m sure the historical figures really talked this way and worse, but much of it seems gratuitous, especially in a book aimed at middle-grade readers. In most cases he could have referred to the bad language without quoting it. Some parents will want to skip the book for this reason, and I can’t blame them.

Betsy: You’re right, Janie—it’s a hard line to find between being “authentic” and including what’s really necessary for the reader. I think many books for this middle grades/early high school market are getting edgier in every respect. It’s important to frequently engage the young readers in our lives in discussions about the books they are reading and encourage them to practice discernment even as we model discernment in our own reading.

Tune in next Wednesday when we discuss a very much honored–and very strange–little novel by Kenneth Oppel: The Nest.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

3 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You mention middle grades, but would this be more suitable for high school students? My 7th grade son is pretty sensitive, so I’m just wondering. I definitely won’t be getting The Nest for him after reading your review. Yikes! I think that book might give me nightmares as well!

Kelli: The book is marketed to middle grades, but I agree it would be more appropriate for high school–not just because of the language, but because of the historical content. Vietnam was a complex situation that developed over several years. Sheinkin does an excellent job of making the situation understandable, but I think it would be challenging for a middle-grader who’s not already a history buff.

Hi my darlin’ Janie. Am reading “I don’t know how this story ends” now in the “john library” Hope you don’t mind my reading room. Looked on Amazon today and they gave this book a rave review. I have just begun but I know I’m gonna like it. By the way, when you were here I mentioned my favorite author – I, of course meant my favorite MALE author John Grisham. You, of course are my favorite female author. Love you a bunch sweetie. My best to Doug, Tielman and Aquila