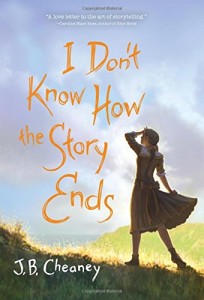

Janie’s sixth middle grades novel, I Don’t Know How the Story Ends, is due to hit store shelves this Wednesday (October 6th)! We will be featuring an interview with Janie about the new book in particular in two weeks (so you all have time to read it before then!), but today we are taking the opportunity to pick her brain on writing in general, be it fiction or nonfiction.

I Don’t Know How the Story Ends is your sixth novel for middle grades/early high school kids (congrats!). Despite the unique stories, there are certain qualities each of your novels share. I especially like your opening sentences and paragraphs; they hook the reader with drama while simultaneously setting up the time and place for the story. I used to tell my students to just start writing and come back to craft the opening of their paper later. Is that what you do, or do those terrific openers just spring to mind when you first begin? (For our readers’ benefit, the opening lines of I Don’t Know How the Story Ends are, “The first I heard of Mother’s big idea was May 20, 1918, at 4:35 p.m. in the entrance hall of our house on Fifth Street. That was where my little sister ended up after I pushed her down the stairs.” Previous novels have opened with similar drama including squirrels in the toilet, a school bus crash, and burning martyrs.)

I Don’t Know How the Story Ends is your sixth novel for middle grades/early high school kids (congrats!). Despite the unique stories, there are certain qualities each of your novels share. I especially like your opening sentences and paragraphs; they hook the reader with drama while simultaneously setting up the time and place for the story. I used to tell my students to just start writing and come back to craft the opening of their paper later. Is that what you do, or do those terrific openers just spring to mind when you first begin? (For our readers’ benefit, the opening lines of I Don’t Know How the Story Ends are, “The first I heard of Mother’s big idea was May 20, 1918, at 4:35 p.m. in the entrance hall of our house on Fifth Street. That was where my little sister ended up after I pushed her down the stairs.” Previous novels have opened with similar drama including squirrels in the toilet, a school bus crash, and burning martyrs.)

First sentences usually come pretty easily to me–that is, once I’ve decided what will be in the first chapter. That sentence about the squirrel in the toilet (The Middle of Somewhere) is based on something that really happened to a relative of mine, but I didn’t know I was going to use that incident until I actually started writing the chapter. (Without going into detail, the mother in that story had to have a non-fatal-but-incapicating-accident in the first chapter, and I didn’t know what it was going to be until I remembered the squirrel story.) With historical fiction, an author has an additional task: not only to get the reader into the story but also into the time and place. I usually don’t include actual dates, but thought I could get away with it this time because the narrator is going to tell about a life-altering summer in her twelfth year, and the “chronicle” touch signals that. The real punch comes in the second sentence, which was not in my first drafts. First-person narrators are often too passive; I decided Isobel’s character needed a bit of aggressiveness. Not to mention a literal push to get the story going.

First sentences usually come pretty easily to me–that is, once I’ve decided what will be in the first chapter. That sentence about the squirrel in the toilet (The Middle of Somewhere) is based on something that really happened to a relative of mine, but I didn’t know I was going to use that incident until I actually started writing the chapter. (Without going into detail, the mother in that story had to have a non-fatal-but-incapicating-accident in the first chapter, and I didn’t know what it was going to be until I remembered the squirrel story.) With historical fiction, an author has an additional task: not only to get the reader into the story but also into the time and place. I usually don’t include actual dates, but thought I could get away with it this time because the narrator is going to tell about a life-altering summer in her twelfth year, and the “chronicle” touch signals that. The real punch comes in the second sentence, which was not in my first drafts. First-person narrators are often too passive; I decided Isobel’s character needed a bit of aggressiveness. Not to mention a literal push to get the story going.

Well, you succeed in pushing the reader into the story right along with Isobel’s sister! Some writing skills and techniques are unique to the particular medium while some are indispensable no matter which medium you choose (prose fiction, poetry, literary nonfiction, journalism, etc.). What are some techniques that work no matter what kind of writing you are doing?

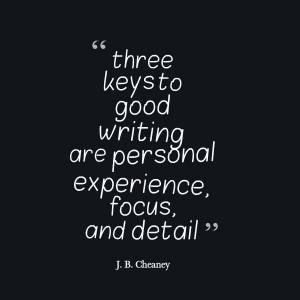

In writing seminars and talks I mention three “keys” to good writing across the board: fiction, nonfiction, review, commentary–even plain ol’ expository. 1) Personal experience: the most direct route to your reader is the life you share, or can imagine sharing. Fiction–even fantasy–should be grounded in realistic human emotions and sensations. Nonfiction is enlivened by personal anecdote and sensory references, which every human being has. Writing is all about communication, of course, but in a secondary sense it should also be about connection. 2) Focus: whatever you’re writing about, keep a tight perspective. A school report should be about one individual, one incident, one experience. Fiction unfolds in specific scenes, not transitional paragraphs. We all tend to generalize too much; it’s the most difficult habit to break. 3) Detail: using lots of details is the practical outcome of experience and focus. In fiction, all of these apply in spades, but the writer is more creative in how she uses them because they are like brush strokes in a painting, all contributing to the overall effect.

In writing seminars and talks I mention three “keys” to good writing across the board: fiction, nonfiction, review, commentary–even plain ol’ expository. 1) Personal experience: the most direct route to your reader is the life you share, or can imagine sharing. Fiction–even fantasy–should be grounded in realistic human emotions and sensations. Nonfiction is enlivened by personal anecdote and sensory references, which every human being has. Writing is all about communication, of course, but in a secondary sense it should also be about connection. 2) Focus: whatever you’re writing about, keep a tight perspective. A school report should be about one individual, one incident, one experience. Fiction unfolds in specific scenes, not transitional paragraphs. We all tend to generalize too much; it’s the most difficult habit to break. 3) Detail: using lots of details is the practical outcome of experience and focus. In fiction, all of these apply in spades, but the writer is more creative in how she uses them because they are like brush strokes in a painting, all contributing to the overall effect.

You have a terrific way of turning a phrase and using similes and metaphors; you also don’t overdo it. Some gems from I Don’t Know How the Story Ends are “my body felt like it had been wadded up and pushed in the corner.” “Sylvia was sticking to him like a wet lollipop.” “…he was so warm to the topic he was popping like corn.” What are your tips for young writers in developing great figurative language like this without overdoing it?

Every beginning writer must make an effort to avoid cliches (like the plague!). “Cold as ice,” “rough as sandpaper,” and “melting eyes” may automatically occur and will have to be resisted. On the other hand, a reader can always tell when you’re trying too hard. Extended metaphors (e.g. “I felt like a sweltering sandwich, spread with humidity between slabs of sun”) almost never work. It takes a lot of finesse to be able to pull them off. Aim for short and punchy, and think and re-think them to make sure they’re not ridiculous. It takes a lot of work to make it look easy! (I’ve written more about figures of speech on my website, especially similes and metaphors.)

Of the many types of things you’ve written, including curriculum on teaching writing, novels for young people, opinion pieces for World magazine, and editorials and reviews here on Redeemed Reader, which are your favorites to write? Is there one example in particular that is your favorite in a given category?

They are all rewarding in different ways. Reviews are probably the easiest and most fun–I love talking about books, especially books I love (and want everybody else to love, too, so we can talk about them more!). Fiction writing is the most exciting, once I get past the huge hurdle of putting a first draft together. After that it’s a voyage of discovery, where you uncover new qualities in the characters and things happen that you didn’t expect. The opinion pieces for World can be the most satisfying–also humbling, on those occasions which I (or the Spirit through me) can reach someone’s heart and cause them to think in a slightly new way.

They are all rewarding in different ways. Reviews are probably the easiest and most fun–I love talking about books, especially books I love (and want everybody else to love, too, so we can talk about them more!). Fiction writing is the most exciting, once I get past the huge hurdle of putting a first draft together. After that it’s a voyage of discovery, where you uncover new qualities in the characters and things happen that you didn’t expect. The opinion pieces for World can be the most satisfying–also humbling, on those occasions which I (or the Spirit through me) can reach someone’s heart and cause them to think in a slightly new way.

What are your tips for young, aspiring creative writers?

A lot of people know they want to write, but don’t know what to write about. Or they have an idea for a great story that seems to peter out to nothing. For both groups, I’d say the first part of writing is looking. And listening. The world is an endlessly fascinating place with unlimited material to write about, if we just stop trying to make everything up! Take note of interesting stories, write descriptions of interesting-looking people, listen for an unusual turn of phrase or dialect. Try writing brief vignettes of scenes from vacations or walks around the neighborhood. Exercises like this will limber up your writing “muscles” and teach you to be observant.

Thanks, Janie! Do YOU have a question for Janie? Put it in the comments! book cover images from amazon; World cover from World

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.