How do you use the label “anti-war?” As in, “Saving Private Ryan is the best anti-war movie ever made, or “All Quiet on the Western Front ranks at the top of anti-war literature.” In 1969, Edwin Starr’s Motown song “War” became a huge hit. Its theme was simplicity itself: WAR! What is it good for? Absolutely NOTHIN’!

How do you use the label “anti-war?” As in, “Saving Private Ryan is the best anti-war movie ever made, or “All Quiet on the Western Front ranks at the top of anti-war literature.” In 1969, Edwin Starr’s Motown song “War” became a huge hit. Its theme was simplicity itself: WAR! What is it good for? Absolutely NOTHIN’!

Frankly, I don’t think it takes much character or imagination to be anti-war. The real challenge is to stare unblinking into the corridors of human history and try to understand why we keep doing this: why such costly, heart-rending bloodbaths, century after century? and why do we insist on writing, reading, and making movies about it?

One hundred years ago this August, all of Europe was mobilized to fight the costliest, bloodiest war to date—also, I think, the most consequential war of modern times. It changed not just the nature of, but also the general attitude toward war—stripped all the glory from it, such glory as there was. After 1914, men would no longer march into battle wearing flashy uniforms and waving shiny swords; instead of gold epaulets and buttons, their clothes would be the color of mud. Instead of weapons with short range and indifferent  aim, they would man guns designed to pour out rapid-fire death and destruction. World War I caught 19th-century people by surprise with 20th-century technology, and it destroyed about one-fifth of an entire generation in Europe. It also set the stage for the next generation to fight an even more destructive war.

aim, they would man guns designed to pour out rapid-fire death and destruction. World War I caught 19th-century people by surprise with 20th-century technology, and it destroyed about one-fifth of an entire generation in Europe. It also set the stage for the next generation to fight an even more destructive war.

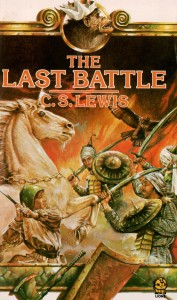

World War I was good for “absolutely nothin’,” and yet, though nobody appears to like it, war still has a powerful hold on the human imagination. It’s a staple of movies and literature. Especially fantasy literature. Even (or especially) Christian fantasy literature. The Chronicles of Narnia begin and end with wars (or at least battles). Lord of the Rings strides from one armed conflict to another, and Andrew Peterson’s Wingfeather Saga winds up with a final showdown between the Wingfeather allies and Gnag the Nameless with his hordes of Fangs. As I was reading it, I thought, “Hey—there are a lot of battles in this story. Is the author glorifying war?”

To write about something, even extensively, is not necessarily to “glorify” it. But yes, in a narrow sense these books do glorify war–of a certain kind. Good and evil are clearly staked out (and often fought out) in all four Wingfeather volumes, even though, as we follow Janner, Kalmar, and Leeli, we become all too familiar with their faults and weaknesses. Their goodness is not so much what they are as who they follow: the Maker, clearly God, who not only creates them but directs them and equips them to fight. The enemy is not a demon, completely black of heart. As we’re let into the villain’s heart, we see how he went wrong and understand that there may be hope even for him. But first he has to be subdued. Giving him what he wants (i.e., not resisting him) allows evil to have its way and produce even more evil. Sometimes, bad people have to be stopped.

To write about something, even extensively, is not necessarily to “glorify” it. But yes, in a narrow sense these books do glorify war–of a certain kind. Good and evil are clearly staked out (and often fought out) in all four Wingfeather volumes, even though, as we follow Janner, Kalmar, and Leeli, we become all too familiar with their faults and weaknesses. Their goodness is not so much what they are as who they follow: the Maker, clearly God, who not only creates them but directs them and equips them to fight. The enemy is not a demon, completely black of heart. As we’re let into the villain’s heart, we see how he went wrong and understand that there may be hope even for him. But first he has to be subdued. Giving him what he wants (i.e., not resisting him) allows evil to have its way and produce even more evil. Sometimes, bad people have to be stopped.

Christians should understand this better than anyone, for Christian faith is in permanent conflict with the rest of the world. That’s why the New Testament is full of military metaphors, and the Old Testament includes plenty of the real thing. Christians gave the world a “just war” theory, where bloody conflict can be justified when one side is clearly in the wrong and intends to do more wrong. Good vs. evil is a theme most of us understand, if we haven’t been “educated” out of it.

But there’s another dimension of war that Andrew Peterson (and other writers, such as C. S. Lewis) address full-on. In an early chapter of The Warden and the Wolf King, Neeli Wingfeather is grieving the losses of a battle and remembering how her beloved hound Nugget had died on an earlier occasion while defending her.

And yet here she was, months later, on another terrible day, experiencing a miraculous lightening of her heart’s burden at the memory of Nugget’s selfless act. It was as if a strand connected that day with this one and the Maker’s pleasure was coursing through it like blood in a vein. Then she thought of this one battle, in which there were countless acts of heroism, sacrifice, and honor, which were seen and which would be remembered long after the heroes died and became points of light in a dark sky, connected by memories like constellations, each of which painted a picture that all the darkness of the universe could never quench. Light danced along the strands.

Irresponsibly romantic? The kind of drivel that “corporations” and “governments” use to lure young men into laying down their lives for narrow, stupid gains? I think the nerve runs too deep to be dismissed as mere exploitation, though warmongers are certainly guilty of that. The way we see things is not necessarily the way God sees things, and He is never cynical. While many (most) wars are incredibly wasteful and pointless, some are not–at least, not pointless. And battle seems to have a deep-rooted appeal, particularly to men (watch this clip and see if you can’t understand it, just a little*). It’s as if men are called to find out what’s in them: savagery or heroism, cruelty or self-sacrifice, the worst or the best. War brought out the best in Louis Zamperini and eventually led him to Christ. Many other young warriors can tell a similar story.

We still pray that our sons (and now, our daughters) will never have to go to war. But we should also acknowledge the appeal, and allow that God may just have a place for it somewhere in the big scheme of things.

What are your thoughts about war in literature? Do you feel uneasy about letting your boys read too much “macho” stuff in comic books? How do you handle violent play-acting in your house? Let us know; it’s worth talking about.

_________________________________________________________

*Now that I think about it, Henry V is actually one of the best expositions of war that I know of. It’s all here: the valor and thrill and heroism as well as the terror, venality, doubt and grief. See a comparison of movie versions here.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I have great appreciation for the way Chesterton approaches war in Ballad of the White Horse.

Such a difficult question. We want to inculcate patriotism and loyalty in our children, but at the same time they are citizens of the kingdom of God first of all. Any patriotism they may feel for their country of origin, however deserved, must be mediated by the knowledge that their state, like every other state or government is by its very structure unable to directly access the kind of leadership that can make its affairs righteous.

Yes, individual citizens can look to God for leadership, and all states have the God-given authority to bear the sword, but every state throughout history whether good or bad has committed the sin of pride, thinking it could either defy God, be God or ignore God. States may imagine good or evil but all they imagine are vain things because states either do not feel the need of God or incorrectly assume they can act for God.

Knowing this, knowing that one must follow one’s civic authority in the duty of defense of the state, many Christians will need to go to war but they may not always have the assurance that that particular war is just or will not result in a worse state of affairs after it is all over. Some will find themselves called to work against their own state. I think we need to be careful of investing our patriotic feelings wholly in the success of our own particular nation. We need to keep in mind that ultimately, God moves and operates in history to save a people and bring glory to himself.

In our own roles in a particular conflict, whether as a statesman or a foot soldier, we must listen to the call of duty as we have light and beg humbly for wisdom for ourselves and our leaders that we would not be led into destruction. Many Christians throughout history have fought on “the wrong side” or have fought losing wars on the “right side” but all fought as citizens of a heavenly kingdom. We may be dismayed, defeated, disillusioned in this present conflict but our eyes are meant to see farther than the protection of a border or the liberation of a death camp.