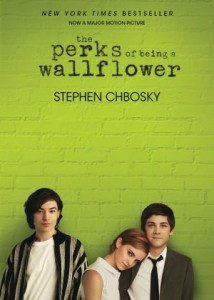

Another popular YA novel is soon to be a “Major Motion Picture,” opening next weekend. It’s not likely to be a blockbuster like Twilight or The Hunger Games, partly because the original book is 13 years old. I am not recommending either the book or the movie, but as a cultural indicator it might be worth knowing about (with spoiler alerts):

The Perks of Being a Wallflower, by Stephen Chbosky. Simon & Shuster, 1999, 213 pages (softcover edition).  Age/interest level: 14-up.

Age/interest level: 14-up.

“Dear friend,” writes Charlie, to a name he picked out of a telephone book. His friend Michael has just committed suicide and Charlie, age 16, has no one to talk to about it. He’s been crying hard. A lot of people “cry hard” in this book, or else they just cry. But they have fun, too. And they have sex. And there’s something a little wrong with Charlie but he himself doesn’t understand exactly what: though very bright and sweet-natured, he can erupt in violence or go catatonic.

The Perks of Being a Wallflower was published at the end of a decade of YA “problem novels” about kids with secret histories or abusive parents or some huge trauma involving death. Perks, which was highly praised and widely read, is the epitome of problem novels: a new contemporary issue bursts out every other chapter (or it seems like it). The story unfolds over Charlie’s freshman year in high school, during which he makes some close friends and falls in love and learns to smoke pot and goes to some parties and runs with a “crowd” and discovers one of his best friends is gay and discovers music (which makes him feel “infinite”) and reads a bunch of books his English tutor recommends—and of course, one of them is The Catcher in the Rye. Charlie is Holden with a history but without the snark. He’s repressed the memories of what his Aunt Helen did to him until the very end of the narrative, but then he gets help and is determined to be okay. He still loves Aunt Helen, and everybody else–too good for this world, we suspect, but he decides to stay in it anyway. Unlike Michael.

All this would be numbing, except for the narrator’s voice, which is often humorous and more self-aware than most teens. Here’s how he describes a lunch-period gripe session:

Sam blamed television. Patrick blamed government. Craig blamed ‘the corporate media.’ Bob was in the bathroom. I don’t know what it was, and I know we didn’t really accomplish anything, but it felt great to sit there and talk about our place in things . . . I would have told the table that, but they were really having fun being cynical, and I didn’t want to ruin it.

And after his first movie date: “[Mary Elizabeth] kept saying it was an ‘articulate’ film. So ‘articulate.’ And I guess it was. The thing is, I don’t know what it said even if it said it very well.”

So there are some insightful observations, but too many “issues”: suicide, homosexuality, pregnancy and abortion (Charlie’s sister—he drives her to the clinic and waits), racism (his grandfather), physical abuse, sexual abuse, girlfriend abuse, repressed memory. It’s too much to deal with adequately in one novel. And then there’s Bill’s reading list: To Kill A Mockingbird, A Separate Peace, The Stranger, Walden, etc. The books are supposed to provide answers, or at least perspective, but none except The Fountainhead are even quoted from: “’I would die for you. But I won’t live for you’ . . . I think the idea is that every person has to live his or her own life and then make the choice to share it with other people. Maybe that’s what makes people ‘participate’” (as Charlie’s therapist has been counseling him to do).

The ending is not exactly upbeat: “I don’t know what I’m supposed to do now. I know other people have it a lot worse. I do know that, but it’s crashing in anyway, and I just can’t stop thinking that the little kid eating French fries with his mom in the shopping mall is going to grow up and hit my sister.”

Well, yes—could be. The line between good and evil runs straight through every human heart, according to Solzhenitsyn. But somehow it seems to have missed Charlie, and perhaps every teen who has ever cried hard may think it’s missed them, too. That’s the danger of teen problem novels: the temptation to identify too closely to the hapless victim. They are not as popular as they used to be, or else a little goes a long way; Speak and The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian are more recent examples of the genre that continue to show up on recommended reading lists, but the field is not expanding. That may be a good sign, if teens realize there’s a limit to feeling sorry for themselves.

Besides a problem novel, Perks may be also classified as a “Literature as Therapy” novel, the downside of which is addressed in “The Use and Abuse of Youth Literature.”

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

4 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Wow. I got whiplash just reading the list of contemporary issues Charlie encounters; how much worse must it be when you’re actually reading the book!

What bugs me about so many “problem novels” is that it defines teens by their problems. In the worlds of these novels, if you have a big problem, like a sexually abusive relative, or a friend who committed suicide, or an alcoholic parent, etc., then you become the book’s Woobie. You are the hapless victim who becomes sympathetic by virtue of having such a tough life. You are encouraged to think of yourself as a victim, because that’s what you are. Dwell on what happened to you. Stew over it. Get angry. You have the right to hate the world and everyone in it, because you have a Problem.

If you are a middle-class kid whose parents love you, who gets good grades and likes your siblings, you are either the Confidante who Doesn’t Quite Understand, or the Fat Cat Hypocrite Who Thinks Everyone Should Toughen Up. You either listen to the protagonist and offer well-meaning but unhelpful advice, or you get sick of listening to the protagonist’s “whining” and tell them to knock it off, after which you go find new friends.

In these books, kids with Problems are normal. Normal kids are lucky and don’t see the world as it is. They promote a warped view of the world, where if you don’t have Problems, you are somehow less of a person than the Victim.

Zing. What an insightful comment.

Excellent comments, Danielle. Thanks for your thoughts!

“I would die for you. But I won’t live for you”

“I don’t know what it said even if it said it very well.”

Oh, the irony!