(Note: This post is reprinted from 2011, in connection with the movie version of Wonderstruck, due to open tomorrow. It’s a larger musing on Brian Selznick’s work in general; if you only want know something about Wonderstruck, scroll down to the book image.)

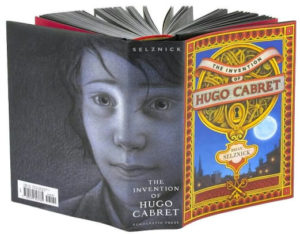

By his own account, Brian Selznick spent six months in a funk before coming across the seminal idea for The Invention of Hugo Cabret. An award-winning illustrator of children’s novels and biographies, he couldn’t see his career going anywhere until he came across a bit of trivia about George Miletes, one of the pioneers of early cinema: it seems the man collected automata (moving mechanical figures) for much of his life, then discarded them. A story idea was born, and eventually, a new way to tell stories. “New” is relative—supposedly there is nothing such under the sun. But Selnick’s way to combining pictures and words to make a chunky volume topping 500 pages is neither graphic novel nor flip book not picture book. Even calling it heavily illustrated is misleading, for illustrations only accompany a story. Selznick’s illustrations actually tell the story, for page after wordless page alternating with sections of text.

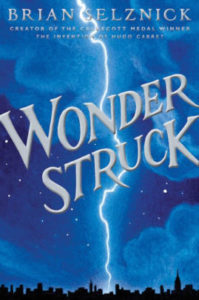

He’s done it twice now: The Invention of Hugo Cabret won the Caldecott medal (generally awarded for picture books) in 2009, but it could just as easily have won the Newbery medal. The day before Thanksgiving, Hugo, directed by no less than Martin Scorcese, will open in theaters nation-wide, which will bump up sales and attention even further. Last summer, Wonderstruck, Selznick’s second novel done in a similar style (only even longer), hit the bookstores and immediately muscled its way to the top of the best-seller lists. The man seems to be on to something, and the books are certainly worth reviewing.

He’s done it twice now: The Invention of Hugo Cabret won the Caldecott medal (generally awarded for picture books) in 2009, but it could just as easily have won the Newbery medal. The day before Thanksgiving, Hugo, directed by no less than Martin Scorcese, will open in theaters nation-wide, which will bump up sales and attention even further. Last summer, Wonderstruck, Selznick’s second novel done in a similar style (only even longer), hit the bookstores and immediately muscled its way to the top of the best-seller lists. The man seems to be on to something, and the books are certainly worth reviewing.

Hugo Cabret, of The Invention, is an orphan boy living in the hidden passageways of Paris’s Central Railway station, keeping up the clocks as his alcoholic uncle (now missing) taught him to do. In between making his rounds and observing the city from behind clock faces, Hugo is working on a project: to restore an automaton rescued by his late father from a museum rubbish heap. In quest of parts, he sometimes steals small mechanical toys from a kiosk in the station. When the elderly shopkeeper catches him and confiscates his priceless notebook, Hugo makes an antagonistic alliance with the man’s goddaughter, Isabelle, to get it back. In between bickering and getting into trouble, they uncover intriguing clues to the old man’s past, leading to the discovery of his past career as an inventor. Not just a dabbler in old technology, represented by the automatons, but also pioneer of a new technology that took the world by storm.

I won’t give the ending away, even though to my mind it didn’t quite deliver on the intriguing questions raised at the beginning. In fact, absent the Wow! factor of the cinematic format, the story itself is rather simple. I say “cinematic” because the drawings—from the dashed and hasty to the richly detailed and textured—work exactly the way a camera does: to build tension, to bridge the action, to foreshadow events, to frame themes and symbols. Even the text pages are bordered in black, like individual frames of film. (The author comes by his camera instincts honestly, being a first cousin twice removed of David O. Sezlnick, legendary producer of Gone With the Wind and other Hollywood classics.)

The story takes place in 1931 but harks back to an earlier day: late 19th century, a high noon of mechanical accomplishment. The automaton is a central figure, seen by Hugo sees as the bearer of a message that “was going to save his life.” Hugo is shown looking out from behind clock faces as though he, with his antique clothes and shaggy hair, has been left behind while the world moves on without him. Is there a place for him? His mechanical bent gives him an answer of sorts. Gazing out over the nightscape of Paris, he tells Isabelle, “. . . if the world is a big machine I have to be here for some reason. And that means you have to be here for some reason, too.” It also implies that someone has created the machine, but we don’t go there.

That’s as close as Hugo Cabret comes to a worldview, and it probably points to a being, force, purpose outside the sphere of earthly time just as Hugo is outside the flow of Paris life. Eventually he finds his place and his purpose, and that’s a good thing—but regarding the Purpose behind the purpose we have no clue. And just what is the “invention” of Hugo Cabret? The mechanical wonders in the story are all inventions of someone else. Hugo takes credit for the book: “These words.” Does that mean we automatons are fearfully and wonderfully made? Or that we have the power to create our own reality?

Wonderstruck includes the scene of new friends gazing out over the night sky, a life-to-scale  reproduction, and lots of movie references, but it tells two stories instead of just one. The first begins in 1977, where Ben Wilson has grown up with a single mom and her sisters’ family in a hunters’ paradise in the north woods: Gunflint Lake, Minnesota. But Ben’s mom was recently killed in an auto accident and his uncle is wanting to sell the house he grew up in—looming displacement. During a lightning storm, Ben finds a clue to his father’s identity—a telephone number. He picks up the phone to call the number just as lightning strikes and renders him deaf in his other ear (he was already deaf in one). Waking up in the hospital, he determines to run away to New York City, where his father may still live, and . . .

reproduction, and lots of movie references, but it tells two stories instead of just one. The first begins in 1977, where Ben Wilson has grown up with a single mom and her sisters’ family in a hunters’ paradise in the north woods: Gunflint Lake, Minnesota. But Ben’s mom was recently killed in an auto accident and his uncle is wanting to sell the house he grew up in—looming displacement. During a lightning storm, Ben finds a clue to his father’s identity—a telephone number. He picks up the phone to call the number just as lightning strikes and renders him deaf in his other ear (he was already deaf in one). Waking up in the hospital, he determines to run away to New York City, where his father may still live, and . . .

Hoboken, New Jersey, 1928: Rose, a deaf child, lives in a world of silence enlivened by the movies. But that’s soon to change with the introduction of talking pictures, and her dismay is poignant—once again she will be cut off from her chief connection with the hearing world. Learning that her favorite movie star will be appearing in Broadway play, Rose runs away to New York City, where . . .

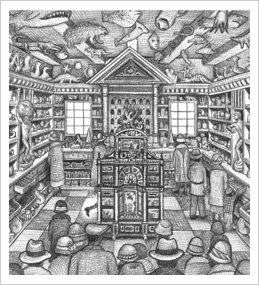

Ben and Rose are separated by fifty years but connected by a disability and a sense of displacement—and more, as it will turn out. His story, told in prose, and hers, in pictures, are intercut in the Selznick trademark way that’s so striking it disguises flaws in the story. Juvenile displacement, as we’ve seen, is a favorite theme of his, and a valid one—we can all relate to some degree. Discovering underlying connections is a great plot device but it stretches a little thin when trying to connect the dots of Deaf culture, silent movies, wolves, the American Museum of Natural History, dioramas, lightning, Grand Murais, “Major Tom,” stars, meteorites, the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens, the 1977 NYC blackout, and museums in general.

At times the story feels like it was assembled from a grab bag of the author’s latest interests and shoehorned into the noble theme of “wonder.” I could see no reason for the secret identity of Rose’s mother, which promises to be more significant than it turns out. Ben’s mother is presented as a free spirit (1977, remember?) but she strikes me as selfish for not telling him about his father. No good reason not to, except that she seemed to want the boy as her own personal possession. Ben’s relationship with Jamie, a boy he meets in the city, is too coincidental and too rushed; Jamie’s need is so intense it’s almost creepy.

At times the story feels like it was assembled from a grab bag of the author’s latest interests and shoehorned into the noble theme of “wonder.” I could see no reason for the secret identity of Rose’s mother, which promises to be more significant than it turns out. Ben’s mother is presented as a free spirit (1977, remember?) but she strikes me as selfish for not telling him about his father. No good reason not to, except that she seemed to want the boy as her own personal possession. Ben’s relationship with Jamie, a boy he meets in the city, is too coincidental and too rushed; Jamie’s need is so intense it’s almost creepy.

The writing is more than capable, even striking at times: “It was as if someone had cut out the dream from his head and put it behind glass”; “Ben wished the world was organized by the Dewey Decimal System. That way you’d be able to find whatever you were looking for . . .” As in Hugo Cabret, the pictures are an endless source of understanding. A kid could spend hours noticing how they focus attention visually and reference each other from one page to the next.

Taken together, Hugo Cabret and Wonderstruck remind me of Marshall McLuhan’s saying about the Medium being the Message: these novels are perhaps too enamored of their format to deliver coherent stories. But still worth a look, and especially instructive for the budding illustrator who could learn a lot about how pictures convey meaning.

Brian Selznek illustrated a worthwhile delve into the history of science with The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins. Somewhat more problematic is his latest lavishly-illustrated novel, The Marvels.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

1 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

If one buys into macro-evolution’s hypotheses of vestigial organs, of chaos organizing itself into higher forms and lesser degrees of randomness, and of mutations that must have resulted in lots of dead-end branches in the ancestral tree, then –-

It’s fine to write plots assembled from a grab-bag of the author’s latest interests and shoehorn them into a theme too broad to be called a plot;

It’s alright to have flaws in the story;

It’s okay if the secret identity of Rose’s mother promises to be more significant than it turns out to be in ‘WonderStruck’; In fact, it’s imperfectly normal for a promising event to turn out to be pointless;

It’s no grounds for criticism that the book develops three or four story-lines but fails to weave them together in the end;

It’s acceptable if only two of the story-lines are brought to resolution and the others are dropped with no fruition;

It’s just fine to portray characters, events, and objects as bearing some significance early in the story, but for them to turn out to signify nothing.

It’s impossible for events to be “too coincidental,” since the whole of reality has been coincidental; The story, like our biological world, only has an appearance of authorship.

But it’s not OK if book sales remain limited to enlightened purchases by public library systems. That’s why stories that evolutionists write retain some vestige of a plot.

Of course, evolutionists would never have come up with the notion of a vestigial organ if they hadn’t believed that a now (allegedly) useless organ signifies something that used to be useful.

When evolutionists evolve to the next level, they will realize that Signs signify nothing significant except to the signer who invented the signs to create his own reality.