Much of our coverage of “Banned Books Week” has centered on the territory known as YA, or Young Adult, which has for the last ten years or so been the glam side of children’s books, if not the entire publishing world. Sales of YA have surpassed adult best-sellers and show no sign of declining: the two that come immediately to mind are Twilight and The Hunger Games. More adults are reading YA, for reasons discussed here. That’s where almost all the controversy over banned books comes to rest: How much is too much for “young adults” (a designation that actually starts around age eleven) to handle?

That question is going to be with us for a long time. Every year another controversy hits the fan, and when we imagine we’ve reached our collective limit as to what’s allowed, there’s always somebody to push the limit a little further, with loud justifications when challenged. When parents or other adults protest a fictional portrayal of incest, self-mutilation, rape, torture, or whatever, we’re told that this is what the world is like. And that’s true—there is no depravity off-limits to the human heart. But is the purpose of fiction only to reflect what the world is like?

Let’s get one point settled: one purpose of fiction is to sell books. Publishing is a business like any other, and while most professionals in the area of children’s publishing do feel a certain sense of responsibility toward their readers, they also have a bottom line to think about. The bottom-line value of the sensational, the fantastic, and the daring is well known; “If it bleeds, it leads,” is not just true of journalism. But once having hurled to the public a novel about a teenage girl bearing her father’s child after a failed abortion attempt, and soon after getting pregnant again as the result of a gang-rape, the publisher will try to justify it by high-minded rhetoric about helping teens deal with the chaos around them. Though it seems far-fetched in the case of that particular novel (and yes, it is a particular novel), is there any validity to that claim? Or to put it another way, just what is literature good for?

Lauren Myracle, in her NPR interview, claimed that teens who don’t have to deal with these extreme problems can learn to empathize with those who do. “Empathy” is often cited as a reason to read fiction, and in some ways it’s a good reason. If a character is presented honestly, warts and all, and the reader has enough discernment to learn from the character, good literature can stretch our understanding of people in general, and even apply some of that understanding to the people around us.

Those are two big “ifs,” however. There’s good identification and not-so-good. An unfortunate tendency in youth literature, going back at least as far as Holden Caulfield, is to portray the youth as a victim. True, young people sometimes are victims of neglect and abuse, but the pernicious element in much of literary victimization, what you might call the “Holden effect,” is to make society at large the persecutor. No one person has harmed Holden; the cause of his angst is the “phoniness” of the world around him, particularly adult phoniness.

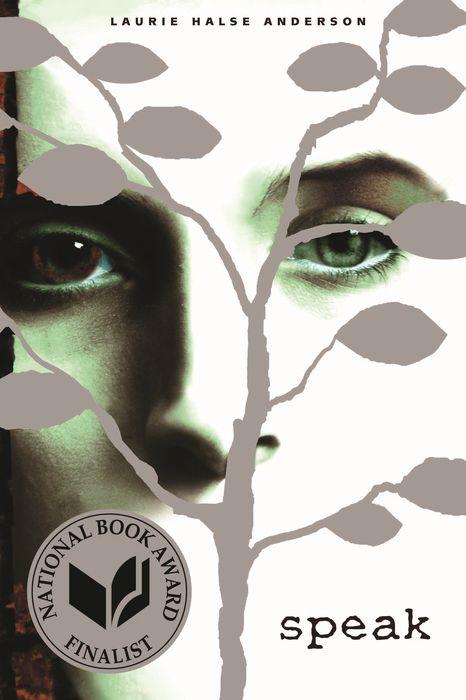

Too many teenagers empathize with Holden*, and that kind of empathy is the wrong kind. Of course parents fail their children; of course society falls short of giving kids something to believe in. But the main problem is within each individual, and most youth literature ignores that. In Laurie Halse Anderson’s much-praised (and much “banned”) Speak, the protagonist’s immediate victimizer is the senior boy who raped her. If Anderson had confined the conflict to that one relationship, Speak might have been a more honest book. But the boy is almost a side issue; Melanie’s entire world lets her down: her parents are totally (and unbelievably) clueless, her counselor is glib, all her teachers except one are preoccupied, and her friends, every one without exception, regard her as a pariah. Melanie’s triumph is to overcome her own feelings of worthlessness and find strength within. The teen reader is on her side from the beginning: she is observant, sharp, and caustically funny (which most teens long to be), and so obviously a person of worth that it’s a badge of honor to join her cheering section.

A more challenging, and potentially more valuable, take on the date-rape scenario is Inexcusable, by Chris Lynch. It’s a story very similar to Speak, but takes the POV of the rapist: a “nice guy” who thinks well of himself and justifies every incidence of questionable conduct—until the end, when he has to face some unpleasant facts. Readers who empathize with him may be forced to ask themselves, Have I ever brushed off an act of cruelty as just a joke? Or naked aggression as healthy competition?

Every challenged YA author, with no exception that I know of, claims that they produce piles of emails and Facebook messages as proof that they’re doing good. “You’ve given me a voice,” is the gist of these messages, from teens who have faced the same kinds of heartbreak and abuse and outright hell that the authors have written about. This goes beyond YA as empathy; we’re now in YA as therapy. Laurie Halse Anderson, again, is almost a high priestess of therapy literature, and I don’t mean that to sound snarky (or not too snarky).

All the same, there’s something a little presumptuous about authors who rush into the supposed void left by parents and the youngster’s circle of peers and adults. Sherman Alexie, as Emily pointed out, does this rather flamboyantly in his answer to Meghan Cox Gurdon’s Wall Street Journal column: “The Best Children’s Literature is Written in Blood.” Really? The best? Little House on the Prairie, The Sword in the Stone, Charlotte’s Web? (“Where’s Papa going with that ax?” asked Fern.)

I would not be so callous as to question any one of the messages these authors receive from hurting teens. Many of them are genuine expressions of turmoil from kids who desperately need guidance, and to the extent that they find real help and inspiration from these books, more power to them. But there’s no way of knowing how many young readers are simply finding confirmation for feeling sorry for themselves. Sherman Alexie’s column bears the tracks of a common misconception: that the more grisly, gritty, or profane, the more “real.” “There are millions of teens who read because they are sad and lonely and enraged,” he writes. If this is true, and “millions” is not literary exaggeration, the sadness, loneliness, and rage is a common affliction of youth that doesn’t need to be encouraged. **

I know that far too many teens are growing up in dysfunctional households; no argument there. But most of them are growing up in the often painful, confusing, ecstatic and stressful transition called adolescence, a rough passage that most will negotiate with some degree of success. It may seem hellish sometimes, but for most kids it is not hell. Better use can be made of these years than focusing on angst and alienation.

If literature is sometimes misleading as empathy and dubious as therapy, what is it good for? Oh, a lot! To “take us worlds away, to take us deep into ourselves, to entertain and delight and stir and frighten and educate and civilize,” as Meghan Cox Gurdon said in her interview with us last week. Good fiction (and really, any form of art) is both a mirror and a window, but it could perhaps be summed up as illumination. Not instruction.

In my experience, art cannot teach; once it starts teaching, it stops being art. It stops convicting and starts informing. If that’s the case, then a reader can only bring to a work of literature what he already knows. What the story or the character can do is breathe life into a lifeless precept. I knew that fathers should protect their daughters, but the failure of Count Rostoff to protect Natasha in War and Peace drove that principle home. I knew that paganism is a dead end, but The Secret History showed me why. If a teen is already empathetic, her reading will re-enforce that. If she’s not, only real-life experience or the intervention of the Holy Spirit will teach her. Sometimes, indeed, the Lord uses a story as a teaching tool–we have plenty of examples of that, in the parables. But the story itself doesn’t teach, which is why the parables had to be explained.

Aspiring fiction writers are always told to “show, don’t tell.” Showing is the purpose of a good story, but the reader will not necessarily get out of it what the writer intends. Writers who suppose that their fiction is shining the light of truth for their readers might have too high an opinion of themselves. At its best, a story can shine a light on truth, but Truth itself has another source.

*In the almost-ten years since this post was written, Holden has plunged in popularity. For one reason only, I think: he’s the model of a privileged, whiny white boy–a true characterization, but interesting that it took antiracism to bring him down.

**Sherman Alexie has also experienced a come-down as an author, due to his alleged habit of hitting on young women at book conferences. His best-known novel is still recommended, as it centers the plights of indigenous peoples, but his person is cancelled–an interesting juxtaposition of political movements.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

6 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Frankly, I thought Speak was a better book for TEACHERS and PARENTS to read than for YA’s. After years of youth ministry and middle/high school teaching, I found Melinda’s voice “spot on” with what many teens feel–regardless of having suffered something as traumatic as she did and regardless of whether those feelings in any given teen are justifiable. It’s important for adults to realize that many teens DO feel like Melinda does (that grownups are completely clueless–even if they are not–she’s not a reliable narrator, is she?). So, in case of Speak, we adults can gain some empathy for teens and perhaps begin to address some issues in their lives (issues being circumstantial–like rape or abuse–and/or more emotional/spiritual).

I also think YA’s are growing up in a different world than we did. Yes, there’s nothing new under the sun, but that nothing new is a lot more accessible than it used to be via the web. Sometimes it’s important to read books like Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian and gain a window into others’ experiences. I, for one, wish Alexie hadn’t provided us with quite so much detail about Junior’s thoughts regarding girls and such, but I did so much appreciate his giving us a character who didn’t wallow in his sordid life–there’s humor, a drive to persevere, and the beginnings of hope/reconciliation at the end.

I agree that much YA literature is sordid, non-redemptive, and not worth reading. But some of it is worth reading and discussing–that’s the key I think–discussing these kinds of books with our teens. John Green, author of Looking for Alaska and other popular (and sometimes gritty) YA books, has a very engaging online presence and kids know who he is–and want to read his books even though their parents might be aghast at some of the content in them.

Sorry to be so long-winded!! I’m passionate about encouraging discussion and honest wrestling with our culture. 🙂

Great stuff, Janie! I’m directing my blog readers to your site today and I’ve added a “Blogroll” link to your site.

Betsy and Glenda, Janie is without internet for a few days, so she won’t be able to comment right away. But I know she’d want me to thank you both for your thoughtfulness!

I too thought the whole YA Saves campaign was rather ridiculous. Not many people enjoy message books and I think it was a mistake for the authors to turn their works into such. It can not be denied that Laurie Halse Anderson likes to write issue books, that is my personal reason for not enjoying her writing all that much. However, I also think people were justifiably angry over Meghan Cox Gurdon’s article that inspired the campaign. The article annoyed me quite a bit too.

The majority of YA literature (and I read a lot of it) is not all that dark. You have your standouts, the ones that end up being challenged, but for the most part the protagonists in YA books are not living hellish lives. I have a list of YA books on my blog that I have reviewed and very few of those could be described as “dark”.

Even of the ones that do have hellish lives I don’t think they “focus on angst and alienation”. I think adult literary fiction does that. YA books usually have a thread of hope running through them even if they are about terrible situations. What Alexie did with Part Time Indian was not only reflect the hellish life on a reservation but showed how hard it was to break free from from a generational cycle of shattered dreams, poverty and abuse. He showed that it was hard, that it would require sacrifice and perseverance, that it would create conflict but that despite that it could be done. And Junior didn’t do it by being all angsty and alienated. Same thing with Speak. I am not a great lover of that book for various reasons but I think what it does show well is that angst and alienation don’t work.

I agree with Betsy that is important to discuss books and take honest looks at the culture around us. Even if elements of it make us uncomfortable.

Excellent post. I’m most interested in the final two paragraphs, simply because I was wrestling with this very thing last week. I was leaning toward the idea that fiction cannot change my mind on anything (it can move something I know from my head to my heart, but cannot change my beliefs about a thing–or as you put it so well, it can breathe life into a lifeless precept, but it cannot teach). But then I changed my mind. If I am in error and the Holy Spirit gives me ears to hear, I can learn truth whether it is presented in a sermon, in scripture, in the words of a friend, through the lips of an add, across the starry night skies, or in a novel.

It is the Holy Spirit that teaches. Through Scripture or through a novel. Now I don’t mean to make the two equal. We know what’s true by looking in Scripture. But if gospel truth is presented in a novel, it’s got plenty of power for salvation, first for the Jew, then for the Gentile.

Don’t you think?

When I came to that conclusion it gave me great hope for my own writing, and it also sobered me.

And I think I know which book you speak of in which the girl is raped by her father. I never read it, but I read excerpts from it when it was in that horrid school library several years ago. I felt dirty for a couple of weeks afterward. There is no justification for writing so graphically.

I am just catching up with your past posts. This is great! I was just emailing someone about my next book (Lady Jane), who has been (wrongly) portrayed as a mindless victim for generations. The idea of victimized young people is as old as the world, and so is the tendency to teach as we write. It will make a good topic for further reflections.