Once upon a time there was no such thing as YA in the publishing world. That may be because there was no such thing as teenhood. A “youth” began taking on adult responsibilities somewhere between the ages of 12 and 18, and adults, young and old, read the same books–either openly or furtively. (I’m old enough to remember smudged copies of Peyton Place being passed between desks and hidden under pillows.) Robert Louis Stevenson, Mark Twain, and Booth Tarkington were considered “youth” authors, but only because their protagonists were young: their readers ranged from eight to eighty.

In the fifties, or maybe a little before, public libraries began shelving series novels with teen protagonists: nurses and “sleuths” and high school girls who fell in love. These were good for passing a summer afternoon when the only alternative was daytime TV, but by the time they reach their teens, children are either serious readers or they aren’t. Serious readers from the age of twelve and over found their way more and more often to the adult stacks, where they began develop a permanent literary taste. Many of them took a run through A Separate Peace, Lord of the Flies, and The Catcher in the Rye (all of which were written for adults) as a rite of passage, but did not shun grownup titles that had actual, you know, grownups in them.

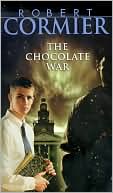

Something changed in the 70s, owing largely to Robert Cormier and The Chocolate War–a novel that I consider to be worthwhile but wouldn’t recommend to everybody.  Cormier wrote it for adults but because of the setting (a parochial boys’ school) his agent urged him to consider marketing it as “young adult.” Cormier had his qualms, because The Chocolate War (published 1972) is unremittingly dark. But it’s also compelling in plot and incisive in characterization, and readers are debating its merits on Amazon.com to this day. Judy Blume, a popular middle-grade author, broke another barrier in the mid-eighties with Forever (which I do not recommend to anybody), an explicit novel about teen sex. Since children’s publishing wasn’t accustomed to posting warning labels on book jackets, more and more books were published under the designation of YA, or Young Adult. The American Library Association created an awards category for it in the late ’90s (the Prinz Award

Cormier wrote it for adults but because of the setting (a parochial boys’ school) his agent urged him to consider marketing it as “young adult.” Cormier had his qualms, because The Chocolate War (published 1972) is unremittingly dark. But it’s also compelling in plot and incisive in characterization, and readers are debating its merits on Amazon.com to this day. Judy Blume, a popular middle-grade author, broke another barrier in the mid-eighties with Forever (which I do not recommend to anybody), an explicit novel about teen sex. Since children’s publishing wasn’t accustomed to posting warning labels on book jackets, more and more books were published under the designation of YA, or Young Adult. The American Library Association created an awards category for it in the late ’90s (the Prinz Award ) and public libraries carved out space especially for teens. The nomenclature was a bit misleading, because serious teen readers were still going for adult books–the actual YAs were mostly 12-15 year-olds.

) and public libraries carved out space especially for teens. The nomenclature was a bit misleading, because serious teen readers were still going for adult books–the actual YAs were mostly 12-15 year-olds.

YA was soon overrun, in the 90s, by “problem” books: neglected boys, abused girls. Speak (Laurie Halse Anderson, 2001), about a 14-year-old victim of rape, was emblematic of the trend. Just about every problem a teen could have was relentlessly explored, with corresponding parental challenges and “bans.” Problem books continued into the “‘naughties” but are less prominent than they used to be. We all know what took their place: first magic (Harry Potter, etc.), then paranormal romance (Twilight, etc.), then dystopia (The Hunger Games, etc.). A supernatural/futuristic element now dominates YA fiction, but there’s another factor that makes it the most dynamic publishing market today: the best-selling YA titles enjoy almost as many grownup readers as teens. A growing number of novels are marketed to adults and teens simultaneously; The Book Thief (reviewed here; scroll down), originally published in 2006 as YA, is currently enjoying best-seller status among grownups. Percy Jackson and other series by Rick Riordan, though written for middle-graders, have a significant number of grownup readers, too.

Why is this? One reason, I’ve read, is simply that teen b ooks are shorter. But that’s not necessarily the case: most top-selling YA novels run to 400 pages and up. A better explanation is that they’re plot-driven: focused on the story rather than psychological analysis or literary flourishes. And another thing: no matter how depressing the story, most of them end with at least an intimation of better things ahead. Hope deferred indefinitely makes the heart sick (Prov. 13:12), and there’s only so much hopelessness we can take. And finally, most of us have a soft spot for youth–our own or our children’s. “There’s something really wonderful about taking the journey with someone of that age,” as the L.A. Times quoted a 36-year-old reader of YA novels. “One of the main reasons I’m attracted to YA literature is just the openness of the characters.”

ooks are shorter. But that’s not necessarily the case: most top-selling YA novels run to 400 pages and up. A better explanation is that they’re plot-driven: focused on the story rather than psychological analysis or literary flourishes. And another thing: no matter how depressing the story, most of them end with at least an intimation of better things ahead. Hope deferred indefinitely makes the heart sick (Prov. 13:12), and there’s only so much hopelessness we can take. And finally, most of us have a soft spot for youth–our own or our children’s. “There’s something really wonderful about taking the journey with someone of that age,” as the L.A. Times quoted a 36-year-old reader of YA novels. “One of the main reasons I’m attracted to YA literature is just the openness of the characters.”

I read very little adult fiction these days, partly because children’s literature is my business–but also because much of it is so darn depressing. Adult authors (and publishers) have only themselves to blame for declining readership, because the authors are either boring their readers with self-conscious “voice” or shocking them to limp rags. Publishers are so relentlessly seeking the next big thing that they ignore their mid-list readers (a not-inconsiderable group) who are just looking for a nice, wholesome story. Like art and culture in general, literature has struck itself out either by pitching too high or too low.

But if more adults are reading YA (and more adult-fiction authors are writing it), the YA category will change. Already pushing limits with language and situation, the supposed “mature” tastes of 30-somethings will knock those limits down and keep on pushing. Expect to see more parental challenges, more “banned books,” more hostility between book professionals and the public.

And another thing that troubles me: once there were no teenagers. Now, I fear, there are fewer and fewer adults. We’re hearing enough about delayed adulthood and kids who live with their parents into their thirties and men who refuse to grow up–we might call them “youngs” instead of youths, for what they yearn to be clashes with what they are, or should be. Might this fever for YA reading be, in some way, a symptom? Many of these books are worth reading, but there’s only so much you can do with a teen protagonist. Grownups face different challenges in different ways, and we need to read about that, too. Instead of youth reaching for adulthood, might adults be hanging on to their youth?

Teens should have some familiarity with the more accessible classics, like Great Expectations, A Tale of Two Cities, Pride and Prejudice, and Jane Eyre. (Moby Dick might be worth a spin, too, though it took me three tries to get through it!) But there’s plenty of good young readers’ fiction being published today, and Lord willing, our recommendations on this site will increase to a sizeable catalog. For one example of age-appropriate fiction with real literary value, see here.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

1 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Interesting article. I know for myself I read a lot of children’s and young adult fare simply because I have grown so weary of starting an “adult” book only to end up having to quit reading it part way through because it inevitably contains so much that is despicably graphic and profane.