Or, the Wordsmith philosophy of teaching composition

Notice I said “simple,” not “easy.” Good writing is based on just a handful of sound principles—that makes it simple. But getting those principles through the head of each individual child is not easy. Or, usually not: some kids seem to be natural born writers with a feel for what makes it work. (Not that certain rules and principles don’t have to be pointed out to them, but once they see it, they’ve got it.) Others just aren’t geared that way: they can take apart a bicycle, calculate in their head, or grasp all the possible moves on a chessboard in two minutes, but verbal dexterity is not their forte. That’s doesn’t mean they can’t learn, only that it will take longer.

Start by Communicating

Writing is a craft, like needlepoint or cabinet-making. Anybody can learn it, but not everybody will be a genius at it. Unlike needlepoint or cabinet-making, however, writing is a craft that all students must learn if they’re going to succeed in school, and perhaps even in life. The bad news is that it takes time. The good news is that you have time.

Public schools make a big mistake, I think, in pushing writing too soon. Just last week someone told me about an elementary school program that was teaching three-point essay writing to first graders. What’s the rush?? Little minds need time to grow and develop and get a firm grasp on good language patterns, and that comes mostly by communicating with their parents. The first step is to talk to them, every day—not just necessary communication like, “Clean up your room.”

Talk about future plans and past mistakes. Tell them stories about your day, and ask for their stories. Talk about sequence, ask for details (“What kind of dog?” “What color was the beach ball?” “What happened next?”). As they learn to read, set aside independent reading time for them. Every day. Ask questions occasionally to make sure they’re comprehending (though not all the time, because you want reading to be a pleasure, and not a “school subject”). Consider discussing with them, whenever appropriate, the books that you’re reading. And keep reading aloud to them, even after they can do it for themselves, because good language should be heard as well as seen.

Continue with Reading

Reading should be center of the language arts study for the early-elementary grades. Of course the kids should learn some form of penmanship, but this doesn’t have to be original composition unless they want to write stories. Taking dictation is great penmanship practice, and programs like Learning Language Arts Through Literature teach grammar lessons along the way. The more you can integrate the mechanics with the usage, the better: see my Laid-Back Grammar post.

Are We Writing Yet?

By fourth and fifth grades, kids are generally ready for real writing assignments, and all that reading in the earlier grades should have already bestowed a sense of sequence, narrative, dialogue, description, exposition, syntax and paragraphing. Upper-elementary children may be more comfortable with writing factual material (exposition) than with imaginative stories or personal essays. If your kids love to write stories, let them—but if they don’t, stick to simple research projects and reporting. Concentrate on complete sentences and coherent paragraphs. If they’re not pushed into premature adolescence, elementary-age students (especially boys) are interested in communicating facts, and don’t care how they feel about them.

That’s likely to change in junior high, when young people start feeling everything, and “creative” writing can be a good way to help sort those feelings out. Given that a 7th or 8th grader knows how to write complete sentences and logical paragraphs (and I know that can’t always be assumed), the focus here is learning how to write effectively. My four basic principles of effective writing are these:

- Use personal experience. A creative writing assignment (as opposed to an expository one) should be based on what the student knows, what she has experienced, or what she can relate to. Don’t ask for her thoughts on family relationships in the abstract before she’s had a chance to write a description of her own grandmother.

- Keep it focused. Generalization is death! Most kids will need a little help with this before they start the assignment, so talk about what the focus should be and how to maintain it. For instance, expound on one element or scene of your favorite movie; write about the one experience of summer vacation that you remember most vividly; explore one quality of your best friend that you appreciate. A bit of general exposition will be needed for context, but should take up no more than a paragraph or two. And for the rest of the assignment?

- Be specific! Use telling details, dialogue, sensory impressions to create a picture. I’ve found it helpful with beginning writers to make a list of guidelines to go along with an assignment. If he’s describing a place, ask him to include an indication of the time of day and season of the year; describe a smell associated with this place; show one or two activities going on, etc. This may seem confining, but it isn’t. It helps the student maintain the focus and gives him tangible goals.

- Finally, teach revision, because no writer writes it right the first time. Learning to evaluate and rewrite is just as important as learning how to write in the first place—in fact, revision can’t be separated from the process.

What about resources and programs? That depends on the kind of learners you have, and the kind of teacher you are. Workbooks, free-writing, story starters, cooperative writing (such as writing a newsletter together), and outlining can all work if the student’s minds are wired that way. Any good program, whatever the approach, should do two things: stress the above four principles, and relate grammar and mechanics to actual writing.

My problem with a lot of workbooks is that students often fail to connect the lesson on “they’re, there, and their” with, you know, actual composition. My own children could get all the exercises correct and still write, “We were to tired to walk the too blocks too the park” in a journal entry. I eventually ditched the workbooks. Instead, we learned about grammar by studying another language (Latin, which helped them appreciate English). We practiced spelling by keeping a personal spelling notebook, syntax by learning to diagram and rewrite sentences, and composition by practice. Maybe good writing genes run in our family, but they still had to learn it.

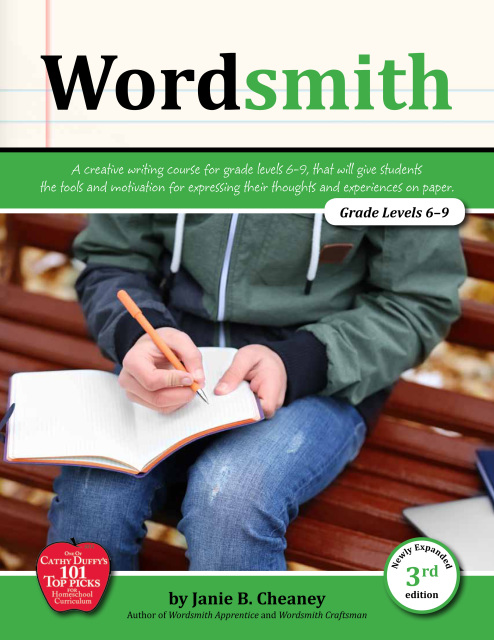

My philosophy and approach to teaching composition are captured in a series of—I’ll have to admit it–workbooks: Wordsmith Apprentice (an introduction for 4th-5th graders), Wordsmith (the four basic principles, for 6th-8th graders), and Wordsmith Craftsman (practical writing and essays, for high school). You can find more information, free samples, and ordering into at the Wordsmith Series website.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

13 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thanks for these tips, Janie. Glad to hear again that reading and thinking are the precursors to composition.

Btw, what is a spelling notebook? My oldest can read on a pretty high level, but when I introduced some simple spelling rules this week, she went limp and nearly started crying. I think I’m gonna back off and wait a little longer. But I may also have to change the approach…hence the question. Is there a way to teach spelling without cramming their heads with rules?

We use Sequential Spelling and it’s great. No rules, just progressive spelling. We started at the start with our daughter who is 12, loves reading and struggles with spelling because of mild Dyslexia.

Thanks for these tips, Janie. Glad to hear again that reading and thinking are the precursors to composition.

Btw, what is a spelling notebook? My oldest can read on a pretty high level, but when I introduced some simple spelling rules this week, she went limp and nearly started crying. I think I’m gonna back off and wait a little longer. But I may also have to change the approach…hence the question. Is there a way to teach spelling without cramming their heads with rules?

Janie: This is a timely article for me. This year for the first time I have decided to…gulp….homeschool my 16 year old son.

The reason is because we were practicing an entrance exam for a local college so he could get dual credit. He did OK on the grammar and reading comprehension but when it came to writing 300 words for or against a specific subject, he was unable to organize his thoughts into a cohesive whole.

His ideas were good but he didn’t know how to break them down, list them in a logical order and support them. That was a turning point for me.

I’m going to start out helping him myself but my sister who homeschools, has given me some good websites that prepare a child to be able to write according to the criteria colleges demand.

Janie: This is a timely article for me. This year for the first time I have decided to…gulp….homeschool my 16 year old son.

The reason is because we were practicing an entrance exam for a local college so he could get dual credit. He did OK on the grammar and reading comprehension but when it came to writing 300 words for or against a specific subject, he was unable to organize his thoughts into a cohesive whole.

His ideas were good but he didn’t know how to break them down, list them in a logical order and support them. That was a turning point for me.

I’m going to start out helping him myself but my sister who homeschools, has given me some good websites that prepare a child to be able to write according to the criteria colleges demand.

Hello! I submitted too soon. I wanted to add that I am bookmarking this article so I can refer back to it through out the year.

Hello! I submitted too soon. I wanted to add that I am bookmarking this article so I can refer back to it through out the year.

Thanks for bookmarking! Not to put too fine a point on it, but Wordsmith Craftsman does address basic organizing issues like outlining and summarizing–even taking notes. I also added something to the post: a link to “Writing Tips” archive on my website.

Thanks for bookmarking! Not to put too fine a point on it, but Wordsmith Craftsman does address basic organizing issues like outlining and summarizing–even taking notes. I also added something to the post: a link to “Writing Tips” archive on my website.

Amen and amen! I don’t know how many times I told my students, “You have to have something to say before you can write.” If we would give kids more of a chance to develop their thinking skills and narration skills (orally), they’ll be much better writers. They also need time to develop their fine motor control so they don’t get bogged down by lack of speed (how many folks can write at the speed of thought?! Typing comes close, but still…)

Amen and amen! I don’t know how many times I told my students, “You have to have something to say before you can write.” If we would give kids more of a chance to develop their thinking skills and narration skills (orally), they’ll be much better writers. They also need time to develop their fine motor control so they don’t get bogged down by lack of speed (how many folks can write at the speed of thought?! Typing comes close, but still…)

Thank you! The important thing is that I know not to force a child without his own will. It’s a very gradual process that doesn’t always go smoothly.

Laney – that’s the first thing writing teachers should recognize. The process takes time, but homeschool teachers have time.