The first time I ever heard my father cry was when my uncle, the brother closest to him in age and disposition, was dying of brain cancer. The process took several months, during which Uncle Charles progressively lost his faculties and faded to a ghost of a human being. I was about 11 at the time. I got up late one night and heard a strange noise from our living room. I couldn’t make out what it was at first, and when I did it felt creepy, shameful, scary. Daddy wasn’t just sniffling; he was sobbing, as though in the grip of an emotion that was wringing him dry.

The first time I ever heard my father cry was when my uncle, the brother closest to him in age and disposition, was dying of brain cancer. The process took several months, during which Uncle Charles progressively lost his faculties and faded to a ghost of a human being. I was about 11 at the time. I got up late one night and heard a strange noise from our living room. I couldn’t make out what it was at first, and when I did it felt creepy, shameful, scary. Daddy wasn’t just sniffling; he was sobbing, as though in the grip of an emotion that was wringing him dry.

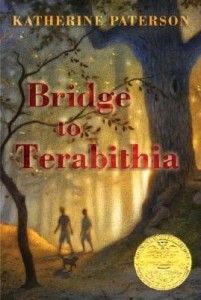

How does one deal with death? Katherine Paterson began writing her classic Bridge to Terebithia in response to a specific crisis. Or actually, two: she had received a diagnosis of cancer a few months earlier, and even though it turned out to be treatable, the very word strikes a chord of mortality deep in the human heart. But then, tragedy literally bolted from the sky when 8-year-old Lisa Hill, her son David’s best friend, was struck and killed by lightning. David was devastated, and his mother was at a loss how to comfort him. Out of their mutual struggle came the story of 11-year-old Jesse Aarons and his best friend Leslie Burke, whose accidental death has shocked, disturbed, consoled, troubled, and stimulated discussion in middle-grade readers ever since.

Bridge to Terabithia won the Newbery Medal in 1978 and a movie version was produced a few years ago, so the story is pretty well known. The only boy in a family of self-obsessed girls, Jesse is lonelier than he even knows until a new girl from the city moves into his rural community. Leslie is very different in background, but after a bumpy introduction the two become fast friends. “Terabithia,” from the Narnia stories, is the name of their secret place in the woods, which Leslie imagines as their private kingdom. One day, Jesse’s favorite teacher invites him on a day trip to the Smithsonian art galleries in D. C. While he is away Leslie drowns in the rain-swollen creek that leads to their hideaway. After learning of the accident, Jesse spins through the stages of shock, denial, guilt, and rage, but by the end of the story he begins to accept his loss.

Terabithia has been criticized almost as much as praised, for a variety of reasons. “Profanity, disrespect of adults, and an elaborate fantasy world that might lead to confusion” is typical of the complaints that have made the novel a perennial on “banned books” lists. Christians have criticized the fuzzy theology, particularly in the chapter where Leslie accompanies the Aarons family to church on Easter Sunday and hears about Jesus for apparently the first time.

“It’s really kind of a beautiful story—like Abraham Lincoln or Socrates—or Aslan.”

“It ain’t beautiful,” [Jesse’s sister] May Belle broke in. “It’s scary. Nailing holes right through somebody’s hand.”

“May Belle’s right.” Jess reached down into the deepest pit of his mind. “It’s because we’re all vile sinners God made Jesus die.”

“Do you think that’s true?”

He was shocked. “It’s in the Bible, Leslie.”

She looked at him as if she were going to argue, then seemed to change her mind. “It’s crazy, isn’t it?” She shook her head. “You have to believe it, but you hate it. I don’t have to believe it, and I think it’s beautiful.” She shook her head again. “It’s crazy.”

Most of us would like to gently take Leslie aside and explain that, yes, it is beautiful in a way, but the crucifixion itself was the ugly result of the wages of sin being laid on the only sinless person who ever lived, and those sins were yours and mine . . . . But this is a story, not a gospel tract, and the conversation as Paterson imagines it is like kids of a similar background might actually have. Raised by free-thinking parents, Leslie has no context from which to approach Jesus and can only compare him to Aslan. “But Leslie,” May Belle insists, “What if you die? What’s going to happen to you if you die?”

That’s not a question Bridge to Terabithia tries to answer but, like most good fiction, it tries to ask good questions. When the novel was published, death was not a common theme in children’s literature. Now it’s a lot more common, especially in YA, but also in middle-grade fiction. Typically, a friend or sibling meets with some kind of accident: in Wenny Has Wings, by Janet Lee Carey, it happens before the story actually begins; in Fig Pudding, by Ralph Fletcher, it’s just past the middle. In Terabithia, the tragedy occurs near the end, leaving little time for Jesse to come to terms with it.

That’s one problem that Barbara Feinberg has with the book. Her memoir, Welcome to Lizard Motel, charts some of her experiences with children’s literature, both as a child and through the experience of her own children. She read Terabithia because it was on her son’s summer reading list, and he seemed to hate it. He dreaded picking it up to read a few more chapters. She wondered why, as the book was beautifully written and the characters appealing. Then she got to the climax, where Jess is curtly informed by one of his sisters that, “Your girlfriend died.”

“I berate [the author],” Feinberg writes: “You didn’t set the death up right. You didn’t prepare us. On some level we have to be prepared.” Feinberg is Jewish, and might not have picked up on the Easter conversation (“But Leslie, what if you die?”). But even if a reader felt prepared, does the author give her enough time to resolve the problem posed by death? Feinberg quotes the novel’s thematic paragraph, where Jesse decides he will not retreat into Terabithia and close the doors, but instead will use what he learned from Leslie to reach out to others. But the resolution seems hurried and pat: “It is as if I’m standing with my ear to the wall trying to make out words muttered from a distant part of the house, barely audible. And then the words I make out are so abstract—‘caring,’ ‘vision,’ ‘strength’—they are not worth the trouble.”

Does Bridge to Terabithia, which is written from a Christian frame of reference though not explicitly Christian, fail in its purpose to redeem a young girl’s death?

I had my son read it when he was about the age of Barbara Feinberg’s son, and while it’s too much to say Tielman hated it, he was not in any way charmed. Unlike his sister, he was not averse to realistic “problem” novels, but the story was too much of a downer, and the ending did not satisfy. Too moralistic maybe; too much “Here’s what we can take away from this tragedy.” Adults can appreciate Terabithia’s artistry and empathy, but pre-teens (or some of them) are not quite ready to process. Feinberg puts her finger on one problem: Jesse has to resolve his crisis totally alone. His father provides some unexpected sympathy, but nobody can really help him. Are most 11-year-olds even capable of coming to a sense of equilibrium within a week, all by themselves?

If I had it to do over again as a Christian homeschool mom, I would focus on that Easter Sunday conversation. There’s nothing inherently beautiful about death. Pop therapy tries to present death as a natural process (as “a part of life”), but it’s not even that. Deep down, we know we were made to live forever, but something really, really bad messed us up. In a sense, we should never be resigned, never “Go gentle into that good night.” Jesus wasn’t, and he didn’t. His quintessential death could not be boiled down to abstract benefits; instead, it was very concrete, a definite act to meet a definite need—and demanding a definite response.

Fiction can’t make that kind of demand. It can’t tell; it can only show. A novelist who’s hoping to reach a general audience–and especially an audience of pre-teens–pretty much has to resort to abstract themes like caring, vision, and strength if she wants to have any kind of positive influence. The difficulty increases in inverse proportion to the age of the reader. That’s why death is often treated as allegory in picture books (the fall of a leaf, the demise of a pet), and goes to soft focus in middle-grade novels (we seldom see the body). And I’m not sure how much it needs to be treated at all. Placing Bridge to Terabithia on middle-grade reading lists may needlessly trouble as many children as it instructs. Of course they’ll have to encounter death sooner or later; death is almost the oldest story in the book, but the central outrage of it never gets old. The outrage is what each individual has to deal with, in his own way and time. For me and my house, the only possible answer is not vague and platitudinous, but terribly specific.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

3 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Lots to chew on here, Janie. Thank you.

I still love this book :-). But it’s not a book I think every kid *must* read (there are very few of those in my humble opinion). I love that Paterson tackles death at all (a rarity in the books I read growing up), that she doesn’t gloss over it–it’s gut-wrenching and hard to understand much like in real life, and I loved the Easter conversation–for the same reason you mentioned: it’s authentic. I hate it when authors use times like that to “give all the answers.” For some reason, fictitious characters discussing spiritual concepts so often comes across as preachy or trite. I’m not looking to fiction to give me all the right answers, but to open my eyes to the right questions–just like you said. And, books like this often cause discussion to spring up among kids/adults.

Treating the death of a young person is a really tough task.

I agree that Bridge to Terebithia doesn’t give a very satisfying

treatment. Where do we get comfort when we have such a

loss? From the adults in our life and from the faith they share

with us.

My youth historical novel, Battle at Blue Licks, treats the death

of Grandma Sarah in a way that brings in faith. The grandson

experiences sorrow, yet has assurance that his grandma is

with Jesus, because she told him so before she died.