Barbara Feinberg’s memoir offers a fresh look at realistic children’s fiction and how much literary suffering children should bear.

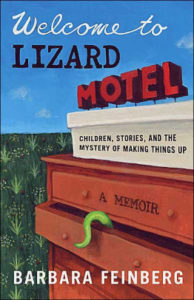

Welcome to Lizard Motel: Children, Stories, and the Mystery of Making Things Up by Barbara Feinberg. Beacon Press, 2004, 207 pages including notes

Recommended for: adults

When Barbara Feinberg, an urban Jewish liberal barely out of her teens, worked at a daycare center on the Upper West Side (Manhattan), she admired her “little troopers.” These were the kids from all economic levels, well-heeled WASPs as well as African-American kids from Harlem. They were dropped off at 7 a.m., sometimes clutching little diaper bags, and often not retrieved until 7 p.m. The day care center was top-notch: casual and comfortable with an excellent staff. Still—it made for a long day without mom or dad or home. But that was life, right? These kids were troopers.

Occasionally Barbara got fired up to give them a dose of relevance. One afternoon she told them about Americans being held hostage in Iran (this was 1979). After waxing eloquent about people being held against their will and children back home missing their dads and moms day after day, she finally noticed someone sniffling. Another child politely asked if they were going to be kidnapped. The current-events review ended abruptly. Why, Feinberg wonders, did it not occur to her that five-year-olds don’t need to be toughened up?

Twenty years later, with children of her own, she noticed her bright, engaged 12-year old son starting to hate the books he was assigned in school: books like Bridge to Terebithia, The Pig Man, and Chasing Redbird. She checked out some of these books for herself, and found them extremely well written and thought-provoking. But . . . they were all about death, sorrow, loss. For a 12-year-old? Certainly, death, sorrow, and loss are part of the package and literature is one important way children have to explore them. But perhaps they’re not quite ready for realistic portrayals, or not in quantity.

Welcome to Lizard Motel (title explained in the course of the memoir) was published just after the era of “problem novels,” when the awards for children’s literature went mainly to books where somebody died, or faced a life-changing trauma, or divorce, or disease, etc. Death and loss drive all literature in a sense, so maybe the content wasn’t a problem so much as its presentation. As she thought further about her son’s reaction (one that his friends shared), Feinberg isolated three characteristics of realistic problem fiction:

- The first-person or limited-focus perspective can be claustrophobic, closing out the wider world.

- Hope is either missing altogether or tenuous and difficult to pin down.

- The protagonist has to work through the issue alone, or mostly alone.

When I read Welcome to Lizard Motel ten years ago, it knocked me off the track of over-serious children’s literature I was headed down (and saved the life of at least one character in the novels I was writing!). I believe there’s a place for novels like Bridge to Terebithia, but also for old-fashioned adventure, goofy humor, and fantasy.

But Feinberg made another point that has stuck with me: children need to know that they are not alone. The self-centeredness that we’re all born with has one positive effect: we believe that the universe is interested in us. After turning this over in my mind for a few weeks I wrote a column for World Magazine with this penultimate paragraph:

Without sentimentalizing the so-called wisdom of children, in this case their instincts are correct. We are not alone. The universe is interested in us. One reason for the phenomenal growth of fantasy literature may be a rejection of the bleakness of contemporary realism. Very bad things may happen in fantasy, mystery, or adventure tales—but the hero is never alone. He or she can count on at least one loyal friend on earth and one supernatural ally beyond. After years of curriculum-directed navel-gazing, fantasy provides a way out via the magic key, the secret book, the quest that takes one beyond himself.

Though she’s not a Christian, Barbara Feinberg’s memoir rings true on many fronts and is a fascinating look at the drama of children’s literature—not to mention the drama of childhood itself.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Sounds like a great book. Something I will definitely need to read. Thank you so much for the review.

You’re welcome, Maureen! I hope you can find it, through inter-library loan, if nothing else.