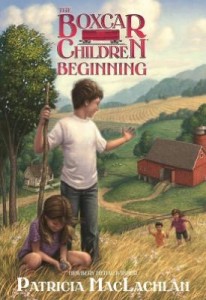

The Boxcar Children Beginning: the Aldens of Fair Meadow Farm, by Patricia MacLachlan. Whitman, 2012,  121 pages. Age/interest level: 7-10

121 pages. Age/interest level: 7-10

The Boxcar Children have had a long run, from 1924 to the present, from nineteen titles by the original author to over a hundred by various other authors. The National Education Association, in a 2007 poll, named the original volume as one of their top 100 books for children—an indication that, with the spin-offs and dramatized versions, the franchise will be around for a while longer. Somehow, I missed them while growing up. I don’t know why; the idea of four siblings setting up house by themselves in a boxcar would have appealed to me enormously. Gertrude Chandler Warner, the creator, was criticized for letting the children do so much on their own without adult supervision. But she knew enough about children, as an elementary school teacher, to understand that they liked to imagine themselves as independent, and stories gave them a chance to do that. “Kill the parents” (usually not literally!) has been a principle of children’s literature ever since.

Whoever had the idea of extending the series in the other direction created a minor event in children’s publishing, especially with the signing of a Newbery medalist to write it. Patricia MacLachlan, author of Sarah Plain and Tall, was a perfect choice for carrying on the tradition, with her spare, simple style and warm-hearted characters. The Boxcar Children Beginning reflects those virtues—almost to a fault.

We meet the Aldens, Henry, Jessie, Violet, and little Benny, living with their parents on the family farm, in the midst of some indeterminate economic “hard times.” Hard times bring them the Clark family, stranded in a snowstorm on the way to Mr. Clark’s father’s house, where they plan to live while looking for work. This adds another mom and dad and two children—plus a dog—to the household. The families meld together effortlessly, and most of the storyline is taken up with school days, meals, little celebrations, and that perennial favorite, “Let’s put on a show!” When the Clarks finally get their car fixed, it’s bittersweet, because the two families have to say goodbye. But in the next couple of chapters, a far more traumatic parting takes place, and devotees of the series will know what’s coming.

The author constructs this slight story carefully, with some poignant moments, such as the children’s discussion about the things they would take with them if they had to leave their home. Good, solid themes are explored without heavy-handedness, such as the value of people over things, the joys of simple living, and making the most of what you have. The things that separate people are shown to be insignificant. Distance, for example: Benny understands where the Clarks are moving and where his own unknown grandfather lives as “just three inches away” on a map.

The storytelling is almost too gentle when it comes to the accident that kills Papa and Mama. The words kill and death aren’t spoken, just, “They’re gone,” after which the Alden kids make plans to set off on their own so they won’t be separated. Adults will quibble: where are the neighbors, bringing food and surrogate moms? Where’s the court system, imposing guardianship? The children’s reaction to their parents death, and subsequent decision to hit the road, are very underplayed–aside from some dignified sniffling, they all display upper lips so stiff you could crack eggs on them. That’s in keeping with the author’s style, as well as sensitivity to very young readers, but in that case, Mrs. Warner was wise to begin the series with the parents already deceased. Young readers certainly shouldn’t be traumatized, but that part of the story needs to be developed a little further, or else dispensed with altogether. Which would of course mean no boxcar, and no boxcar children.

The setting is ahistoric—events hint at the early 20th century but the illustrations and harmonious race relations (the Clarks are a black family) look like the deliberately stereotype-busting 1970s. That’s okay, but a little disconcerting to someone like me who takes a keen interest in history. And another reason why this story, which has many virtues, leaves me with the sense that it could have been better.

- Worldview/moral value: 4 (out of 5)

- Literary value: 3

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.