As Jesus takes us to the cross this week, I’d like to spend some time looking at recent and classic children’s literature that addresses the subject of death. Please understand that I make no blanket recommendation of these books, especially the one I’m reviewing today, which contains some bad language and sexual situations (and the review contains necessary spoilers–there, you’ve been warned). But they all have some merit, at least in helping us understand how the world deals with death.

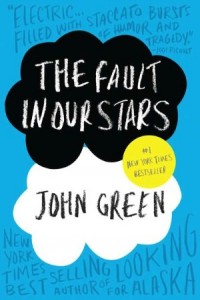

The Fault in Our Stars, by John Green. Dutton, 2012, 313 pages. Age/interest level: 15-up

The Fault in Our Stars, by John Green. Dutton, 2012, 313 pages. Age/interest level: 15-up

Love Story, that late-sixties hankie-wringer, started something like this: “What can you say about a girl except she was beautiful and you loved her and she died?” John Green isn’t going to fall into such sentimental claptrap with his tough-minded narrator Hazel Grace Lancaster, age 17.

She’s the one with the fatal disease, a rare form of thyroid cancer that almost killed her once and is now circling around for a final assault. That’s why she’s going (i.e., her mom is dragging her) to a kids’ cancer support group in a cross-shaped Episcopal church. The group meets in the center of the sanctuary, where Jesus’s heart would be. Group leader Patrick, whose cancerous testicles have been removed (have fun with that, kids), likes to call their meeting place the “literal beating heart of Jesus.”

Hazel’s only compensation for these meetings is Isaac, a teen who’s already lost one eye and stands to lose the other. But one day Isaac brings a friend—Augustus Waters, a survivor of osteosarcoma and incredibly hot, in spite of one missing leg. Instant attraction, plus instant bonding involving Hazel’s favorite book. This is An Imperial Affliction, by Peter Van Houghton, the only author who seems to know what it’s like to be dying without having died. Hazel and Augustus share books, they share fears, they share witty observations in improbably facile dialogue, and of course, they fall in love.

Augustus spends his Genie Foundation wish on a trip for himself, Hazel, and her mom to Amsterdam, where Hazel’s favorite author is reclusing: a dream vacation that quickly runs aground on the rocky coast of Van Houghton’s vile personality. But the trip is redeemed by a visit to the Anne Frank House—another doomed teenager. After this, the lovers make love for the first time: “The space around us evaporated, and for a weird moment I really liked my body; this cancer-ruined thing I’d spent years dragging around suddenly seemed worth the struggle, worth the chest tubes and the PICC lines and the ceaseless bodily betrayal of the tumors.” But their first time is almost the last time, because, as it turns out, Augustus has experienced a relapse and his supposedly-contained cancer has broken loose and run amok. Instead of one doomed lover, we suddenly have two.

John Green struggles to make something positive of this without reference to any creed beyond gut-level feelings, such as Gus’s intuition about a “capital-S Something.” This is driven partly by fear: “If you don’t live a life in service of a greater good, you’ve gotta at least die a death in service of a greater good, you know? And I fear that I won’t get either a life or death that means anything.” The implication is that Gus’s life meant something, even if we have to wrest the meaning for ourselves. At the funeral, Isaac says this about his friend: “A day after I got my eye cut out, Gus showed up at the hospital. I was blind and heartbroken and didn’t want to do anything and Gus burst into my room and shouted, ‘I have wonderful news! . . . You are going to live a good and long life filled with great and terrible moments that you cannot even imagine yet!’”

I can imagine John Green himself bursting into that hospital room with this wonderful news. I met him once at a library conference, and he’s a delightful  person: exuberant, outgoing, generous. His personality is freely accessible through the series of “vlog” (video blog) installments he carries on with his brother Hank: exchanges that are funny, imaginative, often crude and profane, and thoroughly conventional in spiritual matters. I recall sitting at the dinner table with John and a mutual acquaintance a few years ago, suddenly tuning in on the conversation they were having. It was about how they didn’t see the need for Christianity to be so bloody–all that torture and sacrifice and crucifixion. My ears tingled; my heart sped up–should I barge in? What do I say? How do I put this? . . . and the moment passed without me saying anything, which I will always, always regret.

person: exuberant, outgoing, generous. His personality is freely accessible through the series of “vlog” (video blog) installments he carries on with his brother Hank: exchanges that are funny, imaginative, often crude and profane, and thoroughly conventional in spiritual matters. I recall sitting at the dinner table with John and a mutual acquaintance a few years ago, suddenly tuning in on the conversation they were having. It was about how they didn’t see the need for Christianity to be so bloody–all that torture and sacrifice and crucifixion. My ears tingled; my heart sped up–should I barge in? What do I say? How do I put this? . . . and the moment passed without me saying anything, which I will always, always regret.

Here’s one reason why Christianity needs to be so bloody: no vague and inchoate “Something” can redeem the collapse of a young man’s beauty and dignity in the ugliness of death. John Green is honest about the ugliness–unlike the author of Love Story, whose heroine dies with a certain wan winsomeness, Gus goes through hell. Green tries to clean up after it’s over, and his skill as a writer is such that the story glows by the last page: the glow of “an elegant universe in ceaseless motion.” His title refers to Cassius’s line in Julius Caesar: “The fault, Dear Brutus, lies not in our stars but in ourselves.” No, suggests the author: the fault is in our stars, not in anything we did or didn’t do—death is certainly not the wages of sin. But at least the stars may be, somehow, aware of us.

Here’s where the Christian faith is different—so counter-cultural, so specific, so this-and-not-that, it takes the Holy Spirit to break down our natural unbelief. Christ is everything. Christ going through the ugliness of death in His own body, for us, is everything. If the literal heart of Jesus doesn’t actually beat, nothing does. If He didn’t die, death is unanswerable. And if He doesn’t live, life is unanswerable too.

- Worldview value: 2.5 out of 5

- Literary value: 5 out of 5

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I’ve debated reading this–the believers I know who’ve read it are echoing your same thoughts. Hmm…

[…] much of the action takes place in room dubbed “The Literal Heart of Jesus” by one of the teen cancer […]