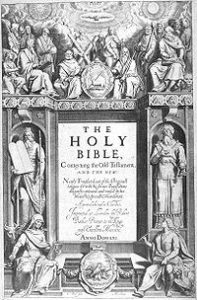

As our readers probably know, this spring marks the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible, and celebrations are going on throughout the English-speaking world. There’s a lot of interesting KJV lore on the internet, as for instance this feature/review from the Times of London. The history is fascinating: the offer of a contentious king to pacify the Puritan sect (which he deeply disliked) by giving them a hand in a new Bible translation led to the assemblage of about fifty Puritan and Anglican scholars. Using not only the original texts but also Latin, French, Spanish, and Italian translations (as well as earlier English versions, such as Tyndale’s), and with little recorded wrangling over literary style, they hammered out a universally-recognized masterpiece of the English language and the most influential translation ever. Not without a few bumps along the road to the 20th century, though: when its influence lagged after the first hundred years, two 18th century refurbishments brought the language slightly up to date and gave the translation a new lease on life. Almost 200 years later, when newer translations were threatening its near-monopoly at the turn of the last century, Cyrus Scofield used the KJV as the basis of his Reference Bible (1909), which became the gold standard of American Evangelical churches for the next fifty years.

As our readers probably know, this spring marks the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible, and celebrations are going on throughout the English-speaking world. There’s a lot of interesting KJV lore on the internet, as for instance this feature/review from the Times of London. The history is fascinating: the offer of a contentious king to pacify the Puritan sect (which he deeply disliked) by giving them a hand in a new Bible translation led to the assemblage of about fifty Puritan and Anglican scholars. Using not only the original texts but also Latin, French, Spanish, and Italian translations (as well as earlier English versions, such as Tyndale’s), and with little recorded wrangling over literary style, they hammered out a universally-recognized masterpiece of the English language and the most influential translation ever. Not without a few bumps along the road to the 20th century, though: when its influence lagged after the first hundred years, two 18th century refurbishments brought the language slightly up to date and gave the translation a new lease on life. Almost 200 years later, when newer translations were threatening its near-monopoly at the turn of the last century, Cyrus Scofield used the KJV as the basis of his Reference Bible (1909), which became the gold standard of American Evangelical churches for the next fifty years.

When I was growing up, the KJV was read from the pulpit almost exclusively, in all churches—whether fundamentalist, mainline, evangelical, or fringe. Sunday school materials and church bulletins and denominational magazines quoted from it; children chanted their memory verses from it; if a household had multiple copies of the Bible they were all likely to be KJV. The tide was already beginning to turn, though. My own mother read to us from the Revised Standard (the most prominent of the few alternate translations available). One of my professors at a Christian college joked that when Philip asked the Ethiopian eunuch if he could understand what he was reading, the eunuch’s reply was, “How can I? It’s a King James Bible!” Someone could always remember an old-timer saying, “If it was good enough for Peter and Paul, it’s good enough for me.”

But that was then. Gideon Bibles are still King James, and the old rhythms persist in the way most of us remember the Lord’s prayer and Psalm 23. But the monolith of the KJV broke long ago, battered by upstarts like the J. B. Phillips translation and Good News For Modern Man, shattered by the NIV. Now the Wall o’ Bibles at any large Christian bookstore are enough to make our heads spin: dozens of translations and paraphrases and scores of repackagings like the Overcomers Bible, the Bikers Bible, the Extreme Teen Study Bible, etc., etc. With so many newer—and more accurate, given modern advances in textual scholarship—translations available, is there still a place for the KJV in your home, school, or homeschool?

I think it’s earned a place. One problem with contemporary Christianity, in any age, is its drive to “make all things new.” I was brought up in a denomination that claimed to throw out all of “man’s traditions” in order to return to a pure New Testament church, but of course there’s no such thing as a Pure NT church—not even in the New Testament. Urban churches, seeker churches, and storefront churches are continually trying out ways to be unchurchy in order to speak to contemporary society. I understand this; it’s the same rationale that broke the domination of the KJV. But in our rush to relevance it’s easy to trash the past and wipe out the footprints that got us where we are.

Christians today are the children (spiritually if not physically) of Christians yesterday, and the day before, and the day before that. We’re part of a long tradition, the earthly contingent of a “great cloud of witnesses” that we will one day join. It’s worth keeping in touch with the past, partly so we don’t repeat their mistakes. But also as a way of paying our respects to the way the Holy Spirit has worked through the ages. He provides every generation what it needs, but leaves the history books open to remind us of His provision. The great hymns, the creeds and confessions, the old language are ways to stay in touch with our fathers and avoid the error of historicism*. We do have to stay current; their challenges were not the same as ours. But a sense of the past gives us a broader platform to stand on.

Back to the KJV: I wouldn’t use it as a study Bible or regular read-aloud Bible. But if your kids do a lot of memorization, I would ask them to memorize some well-known passages from the KJV. A unit on the history of the English Bible would be instructive (wish I could name one—any suggestions?). Compare Hebrews 11, Psalm 100, John 1, and other iconic passages in the KJV and in another translation, and analyze the language: not just which is more understandable, but which sounds better when read aloud? Which is easier to memorize? What words have changed, and in how many cases does the change seem to be for the better?

The story of the Authorized Version is one of those providential true tales that shed enormous light on culture and history. It’s worth knowing, and so is the book itself.

*The meaning of historicism can be stretched, but I’m using it in the sense that ideas or virtues are only valid to their own time; i.e., there are no enduring principles that apply to all ages. In its most extreme form, it claims that dead white guys have nothing to say to us.

Support our writers and help keep Redeemed Reader ad-free by joining the Redeemed Reader Fellowship.

Stay Up to Date!

Get the information you need to make wise choices about books for your children and teens.

Our weekly newsletter includes our latest reviews, related links from around the web, a featured book list, book trivia, and more. We never sell your information. You may unsubscribe at any time.

We'd love to hear from you!

Our comments are now limited to our members (both Silver and Golden Key). Members, you just need to log in with your normal log-in credentials!

Not a member yet? You can join the Silver Key ($2.99/month) for a free 2-week trial. Cancel at any time. Find out more about membership here.

1 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

A similar anecdote:

We have a friend from seminary (he is now getting a Ph.D. from Oxford in O.T. languages) who preached one Sunday using the Hebrew Bible. After church, one of the men came up and asked, “Which translation of the Bible were you reading from?” Our friend answered, “I was reading from the Hebrew.” The man said, “I don’t know about that, but here we use the King James!”

And I agree that there are passage that just seem to “stick better” when you memorize them from the King James.